rewrite this content and keep HTML tags

On Feb. 28, 2023, Evil Geniuses’ 19-year-old ADC Kyle “Danny” Sakamaki, who had been widely considered the next star of North America’s League of Legends esports scene, stepped away from the LCS due to the overwhelming pressure of being a pro player. Less than three years after his debut, Danny said he had reached his breaking point, but he’s not the only player who’s had to shoulder this burden since his teenage years. The pressure felt by Danny is all too common for pros across all esports, including those in the LEC.

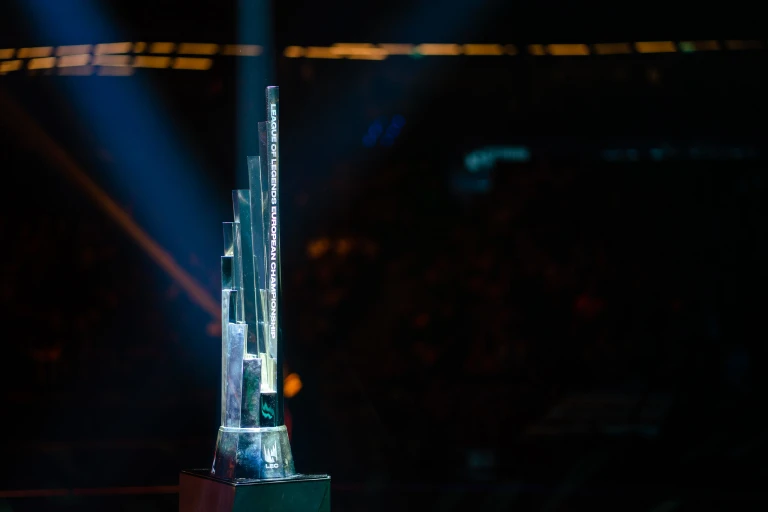

The earliest a player can compete at the highest level in EMEA League is 17 years of age, as per the official rules of the 2023 competition. But pursuing the passion of playing video games as a career often comes at the expense of the mental well-being of players who aren’t even adults yet.

More and more frequently, pros have retired due to physical problems or mental burdens, but little is known about what they go through behind the scenes. Depression, burnout, insomnia, addictions, and isolation are some of the struggles these teenagers and young adults experience as they pursue their dreams, issues too often overlooked because of the superficial idea that these athletes are just playing video games.

Dot Esports spoke with 16 current and former LEC players about how a pro player lifestyle has impacted their mental well-being and their own experience with the organizations they’ve played for throughout their careers. Some names have been changed to protect their identities.

The life of a League pro is a roller coaster of high highs and low lows. While the wins can send players over the moon, the losses make them feel it’s the end of the world. A split lasts just over a month in the current LEC format, leaving pros little room to focus on anything besides League.

Current top laner for Astralis, Finn Wiestål, told us players don’t have “a lot of room for mental stability” once the split starts because they have to give their all to the game or fall behind. Losses only aggravate uneasy feelings as doubt starts creeping into the minds of the pros.

“You are supposed to be good, but you’re not for some reason,” Yasin “Nisqy” Dinçer, current mid laner for Mad Lions, told us. “It’s very rough to come back mentally and be confident in yourself. At the end you might be thinking, ‘what is this job I’m doing if I’m just losing?’”

The mid laner recently faced backlash from the League community after showing a positive attitude after a tough loss at MSI 2023, a ruckus that prompted a response against online harassment from his organization. Before the competition began, Nisqy had said to Dot Esports that it’s difficult to see the real struggles of pro players from the outside.

With only nine games to make a positive impression on the people who hold the power to bench them, pros are put under much more pressure to win than if they had weeks to showcase their talent, increasing the chance of performance anxiety. While this packed schedule for the new LEC format had been greenlit by organizations and players, some still believe it was a step in the wrong direction for player well-being.

“[The new format] is fucking shit, not gonna lie,” said Daniel, a veteran player whose name has been changed to protect his anonymity. “That’s just a business conveyor,” he added, saying the change to the format removes the “honeymoon” phase between a team and a player, the first few weeks where teammates get to know each other and their playstyles. According to him, this can lead to careers collapsing from the pressure early in the season, possibly ruining their shot at a long career in the top leagues of LoL.

According to most of the interviewed players, gaming isn’t the most stressful part of the pros’ lifestyle. Throughout their careers, most felt at their worst during the off-season, when their destiny lay in the hands of the organization they have a contract with. Pros know working in a competitive field comes with the risk of being replaced if better players emerge, but knowing this doesn’t make the prospect less daunting.

A player who we’ll refer to as Chris told us that getting benched was what hit him the hardest. “At that point, my self-esteem was based on my performance,” he said. “If I won or played well I would feel good about myself, but if I lost I would feel worthless and have no confidence anymore […] It was a very depressing time for me where I felt worthless and had no purpose. I was not mature enough to deal with the situation and just made it worse.”

Tim Reichert—founder of SK Gaming, current CEO of EXCEL, and former professional football player—also highlighted the lack of education as part of why the mental aspect of the life of an esport pro is much more challenging than a traditional athlete. “Most esports athletes lack a proper education and learning curve on how to become professionals,” Reichert said. He pointed out that while most traditional athletes are exposed to the path to pro from a very young age with plenty of role models to follow, esports pros have “limited educational resources on how to behave and prepare like professionals.”

The need to “figure things out on their own” as teenagers and adapt to a lifestyle many know little of carries risks for their mental health, as these young adults adopt a very stressful way of living in pursuit of their dream job. While some players claim orgs are slowly becoming more capable of helping them deal with the mental load, others are finding it hard to ignore frequent systemic failures.

“I’ve seen a player being so burned out that he wasn’t able to get out of bed anymore,” Chris told us. “He had been living and breathing League for so many months without anything on the side. His brain eventually couldn’t take it anymore and he wasn’t able to play for two weeks. I’ve seen many players burn out, but nothing like that.”

Daniel said “all the mental problems” are just part of the life of competing at the highest level. Experience helps most learn to deal with harsh comments, negative feelings, and toxic environments, but he also tells us about the abuse of alcohol, snus, cigarettes, marijuana, “too much caffeine,” and food as coping mechanisms. “Everything I saw was from veterans,” added another pro, suggesting it’s not only the teens who struggle.

“I am one of those players,” Nisqy said. “Not that I use anything dangerous, but I don’t hide it from anyone.” The mid laner shared that he smokes and goes to hookah lounges, things that are as normal to him as going to the gym or playing sports. He believes everyone knows their limit and as long as their substance use isn’t exaggerated, everyone should be free to do whatever they want. Similarly, his teammate Javier “Elyoya” Prades Batalla said the usage of certain substances is a just a bad habit or vice for some individuals, not a way to escape the pressure of their jobs.

Current bot laner for Team Vitality Elias “Upset” Lipp confirmed players do use unhealthy ways of escaping these mental pressures, but declined to share more on the topic. Another LEC pro admitted he started drinking during the most depressing year of his career. This made him feel happier than usual, but he doesn’t believe any player is using alcohol as an escape.

Daniel doesn’t agree, however. He believes drinking to be an issue spread among pros. “I played with several players who had a drinking problem. On off days they went completely crazy to forget the pressure. If it was a super bad day in scrimms, they would chug ten beers just to go to sleep as fast as possible,” he told Dot.

He explained this is one of the reasons a lot of organizations “force” players to go to the gym or do physical activity. Studies, like the Physical Activity and Health Promotion in Esports and Gaming (2021) and the Physical Exercise and Performance in Esports Players: An Initial Systematic Review (2023) have shown evidence that physical activity positively modulates anatomy, physiology, and brain function, improving cognitive performance in esports players—making physical exercise a must for all professional teams to include in the pros’ training regimen.

Physical activities can enhance the quality of life of pro athletes all around, but the looming threats to their careers are mostly tied to psychological pressure often coming from the same people and organizations who vow to help them achieve greatness.

Throughout their careers, LEC pros play in rotation under one of the 10 organizations that have full authority on whether a player is walking on stage, getting benched, or being taken off the team. Most of the time, the orgs’ choices are not discussed directly with players, and there are cases where said choices are a product of negative interpersonal relations between staff and player—usually leading to pros being benched or replaced.

Daniel told Dot that he had a former teammate who had a contractual issue with their former organization. He couldn’t be fired, but the org didn’t want to work with him anymore. “It was like a mental war,” Daniel recounted. “My friend was so stressed, he had insomnia because of it. It was an insane situation. It looked like a mental disease.”

Neither of the two parties were willing to give up, and the situation persisted until his former teammate had to leave the team because of health concerns. “He was basically not sleeping more than two hours a day for three months. When he went to [another org], he started performing way better,” Daniel said.

The environment created around pro players by their teams and organizations has as much of an impact on their mental well-being as their performance in competitions. Most players leave their hometowns to move to a bigger city, often joining the organizations’ gaming houses where they can live and work with their teammates. While it’s known that some LEC organizations actively take care of their players’ mental well-being by partnering with psychologists or working with performance coaches, this wasn’t and still isn’t always the case.

“It’s a competitive business and you can’t make sure everyone is okay all the time,” Chris said. Having played with several organizations over many years, Chris said he had to learn how to deal with his mental struggles by himself to avoid bothering anyone.

Finn, like other pros, shared that “more often than not,” orgs give players the option to have a person to talk to—someone who works for the team or an external partner. But from what he can tell, a lot of players “neglect” the option and choose to deal with their problems on their own, as Chris did. And even when pros choose to open up to the team’s staff, there are issues that can arise within the team unless a solid relationship of trust is quickly built between the parties, and the best way to do so is to have a professional working close to the players.

In a statement to Dot Esports, the LEC said it was working closely with teams and tournament organizers to understand and “continuously improve” players’ welfare. “This is an area of ongoing development and one that we are committed to further enhancing in the future,” a Riot Games’ spokesperson wrote.

Seven out of 10 orgs in the LEC have an in-house specialist helping pros optimize their performance by combining mental and physical training. But it doesn’t matter if some have a PhD in psychology if they cannot build a relationship with their players, as said by Martina Čubrić, sports psychologist at MAD Lions, in a past interview with Dot Esports. She works closely with the team’s coaching staff, and even closer with Jake Ainsworth, MAD’s performance manager.

Over the years, the duo refined their approach to players and how to aid their physical and mental well-being. But ultimately, staff need to start over every time someone new signs with the team. Ainsworth had explained how there are a series of observation tests he and Čubrić do to “sort of gauge where [players] are at” when they join. And then it’s a matter of getting to know them, observing them, noticing their habits, having conversations to obtain information used to understand what the team can do to help the player improve.

Nonetheless, various players claimed organizations tend to prioritize the well-being of their business over that of their own players. “I have not met many helpful and nice people in my time in esports that seem to care about the human side more,” Upset said. “But it completely depends on which person you encounter.”

Both players and orgs alike know mental health support has room to improve, and although pros’ experiences were not always positive, they can see some organizations making efforts to create a space where the mental well-being of a player is protected. Other pros, though, have already lost faith in the LEC organizations.

“There is a meme about it,” Daniel said. “When you join the team, they say you’re family. But when they kick you, they say it’s just business.” This veteran said the focus on “money and business” in European organizations can make the relationship between staff and players “much more brutal” than it is in other regions.

“Not every player is treated equally,” he continued, pointing at how the orgs will change their attitude depending on whether they’re talking to a “golden player” or a “weak link.” Sometimes the unwelcome news is given in a humane way, so a player can understand the reasoning behind it. Other times, they just tell them they’re “fucked.”