MILLS LANE died last week at the age of 85, some twenty years after being told by doctors that he’d be lucky to survive another five when he suffered a stroke in 2002. That he lasted so long, or indeed survived the stroke in the first place, should be no surprise to those who knew the tenacious little southpaw that found worldwide fame as a boxing referee.

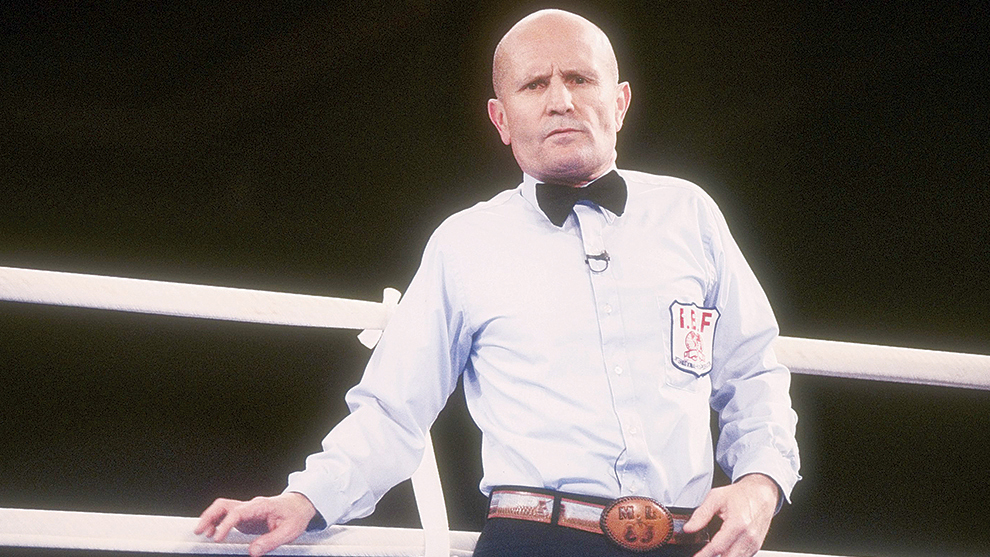

Fight fans who followed the sport in the 1980s and 90s will remember Lane well. His catchphrase, “let’s get it on!” (the antithesis of the Marvin Gaye track of the same name) was every bit as familiar as Michael Buffer’s “let’s get ready to rumble” and the no-nonsense manner in which Lane handled some of the biggest fights of that era saw him elected into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2013. Ferociously bald but short in stature which was exaggerated when regularly wrestling with heavyweights like Mike Tyson, Evander Holyfield, Lennox Lewis and Riddick Bowe, only Richard Steele could rival him as the most recognisable official of his time. In fact, unlike Steele, Mills transcended the sport – no small feat for a referee – when the MTV animated series, Celebrity Deathmatch, featuring an eye-bulging caricature of Lane spitting out his catchphrase, achieved significant popularity in the 90s. That was soon followed by his own TV courtroom show, Judge Mills Lane, which ran for a whopping 700 episodes.

“Let’s get it on!” was first uttered ahead of the Larry Holmes-Gerry Cooney fight in 1982, some 11 years after Mills’ debut as a world championship referee. “I wanted to do something different,” Lane later explained. “It was always, ‘shake hands, good luck, blah blah’, I felt it was time for something different.”

Alongside the catchphrase, Lane would often touch his nose and point to the camera as he was announced to the crowd. That gesture was for a close friend afflicted by cancer, to whom Lane wanted to make clear was always in his thoughts.

In November 1937, Mills Lane III was born into a wealthy family in Savannah, Georgia. His grandfather, Mills B. Lane, had previously founded the largest bank in the state. His father had big ideas for young Mills and paid for his son to attend Midwestern University where he was to study agriculture before, they hoped, finding his way into the world of banking. But by the time he 21 years old, Lane chose his own path. He left university and enlisted with the Marines in 1958. It was while on service when he learned how to box.

When his time in the Marines was up, he enrolled at Reno’s University of Nevada, largely because it had one of the best boxing teams in all of America. While there he won the NCAA welterweight championship – “I tell you, it was the thrill of my life,” he later reflected – and, in 1960, reached the semi-finals of the US trials for the Olympic Games. He turned professional as a welterweight in 1961, lost his debut before winning his next 10. He was 29 years old when he retired in 1967 with a respectable record of 10-1 (6) – though Mills would later claim his record was in fact 11-1-1.

He was the first to admit he wasn’t the most skilful of boxers, relying instead on a huge heart to get him through. The debut loss left him sick to his stomach. “Show me a good loser,” he said, “and I’ll fight him every day.” His gung-ho style ultimately left him without any cartilage in his nose.

Always fit and feisty, Lane made no secret of his displeasure when boxers did not look after themselves between fights. A few months after refereeing Donald Curry’s stunning two-round blowout of Milton McCrory in 1986, Lane bumped into the then-welterweight king. Curry looked heavy and admitted he weighed 162lbs, some 15lbs over the welterweight limit. Lane, never afraid to speak his mind, said to Curry, “What are you doing, man? You work in TV, you don’t leave your camera and lights out in the rain do you? You don’t abuse your tools. When you’re a boxer, your body is your tools. Don’t abuse your tools!”

He had a sense of humour, too. When he met his third wife and now widow Kaye for the first time he swore at her, with a tongue in his cheek, when she suggested he was short. Former Ring editor, Nigel Collins, said on Twitter: “Although I’ve interviewed Mills Lane and watched him referee many fights, what I recall best was what he said to me when I wished him luck before a fight he was working: ‘I’ll be OK as long as I don’t trip over my dick.’”

The world of law was his other great passion and, while learning his trade as a referee, he worked as a prosecutor and later, as a district attorney and district court judge. That desire for justice was perhaps Lane’s greatest quality, so too his ability to restore order when only chaos loomed. He was the man who threw out Tyson in the Holyfield rematch in June 1997, did the same one month later to an unwilling Henry Akinwande against Lennox Lewis and, when Oliver McCall couldn’t keep the tears at bay, he raised Lewis’ hand in their return. He was also there when the ‘Fan Man’ landed in the ring during Holyfield’s sequel with Bowe.

Asked why he stopped the fight after throwing out Tyson for the second bite on Holyfield, a furious Lane said at the time: “How many times you want him to get bit? There’s a god damn limit to everything you know, including bites, that’s why.” When it was then put to him that Tyson had claimed he was being butted by Holyfield, Lane barked, “Bullshit! The butt was unintentional and I called it as such.”

Lane adored boxing and, in a world of murky characters, his integrity always shone through. It is with sadness that we say goodbye to one of the best officials of them all.

“Mills Lane was as good a man as I’ve known in boxing, or anywhere else for that matter,” said Lou DiBella. “A bright, passionate, ethical and principled person, he always gave and commanded respect. His stroke was a true tragedy that left this legend a prisoner in his own body. He is free now.”

Mills Lane leaves behind his wife, Kaye, and sons Tommy and Terry.