By Oliver Fennell

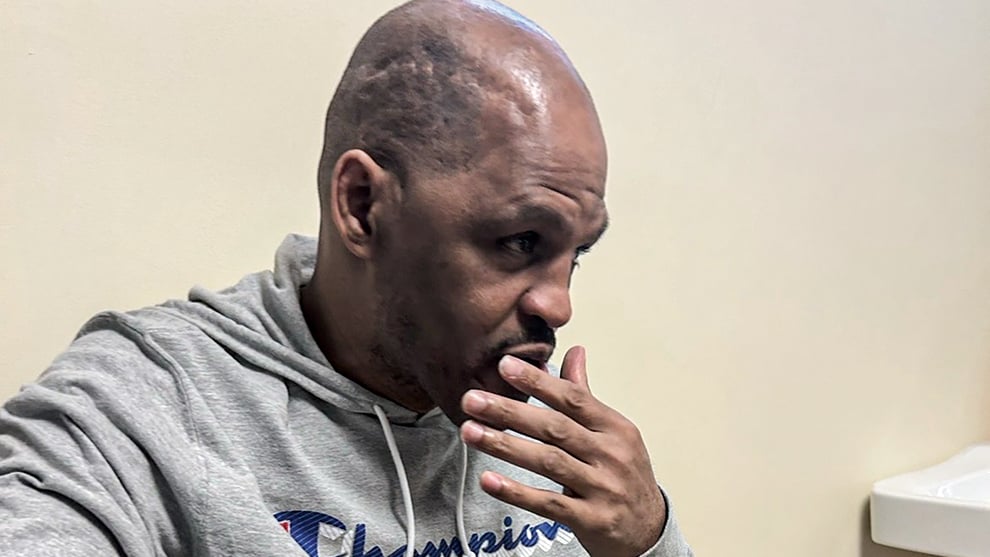

THE legs that once carried one of the most intimidating and powerful boxers into and around the ring are now withered through misuse. The hands which once formed fists that punished opponents now reach out in search of comfort and connection, taking the place of eyes which once tracked prey but now no longer see anything. The body, once honed to athletic perfection, and which once travelled the world, is now confined for almost the whole day, every day, to an armchair. And the brain, once focused with the intensity of a hunter, which once crafted and executed world-class strategy, is now hopelessly broken, stuck in decades past, and largely unable to store new information.

He asks the same questions over and over again, and repeatedly announces the same information, with justifiable pride, that shows he at least still knows who he is and what he has accomplished.

“I’m Gerald Allen McClellan Senior! My position in boxing: middleweight champion of the world!”

Gerald ‘G-Man’ McClellan won the WBC title in May 1993 with a fifth-round knockout of Julian Jackson. Even before then, he was already regarded as one of the sport’s biggest punchers. The Jackson win confirmed this reputation, and three title defenses, all over within the first round, underlined it.

“Ask me what my record is.”

“What’s your record?”

“Twenty seconds!”

He punches the air, grinning widely. “Fastest knockout in history!”

One of those three defenses was the 20-second finish he’s referring to; a one-punch KO of Jay Bell in August 1993 which was at the time the quickest ‘world’ title bout ever recorded. It added to a growing legend that Gerald took with him up to super-middleweight and across to London when he challenged his 168lbs WBC counterpart Nigel Benn on February 25, 1995 – one of the most fateful nights in boxing history.

McClellan and Benn’s fight was among the most violent the sport has ever seen. The only thing more awesome than the spectacle of Gerald’s firepower was Benn’s refusal to wilt under it. When Benn, a marked underdog, somehow clawed his way to victory, it should have been one of boxing’s brightest nights; instead it was one of the darkest, and a darkness from which McClellan has yet to emerge, 29 years later.

“Steven?” he asks as I take his hand. His grip in return is strong and eager.

“No, I’m Oliver.”

“Oliver? Full name?”

I tell him, and then I tell him again, louder, then again, louder still, as he continually asks me to repeat it, louder, louder, and he pulls me closer to the side of his head, where a long, arcing scar traces the path where surgeons at the Royal London Hospital had cut open his skull to remove from his brain a massive blood clot that had formed and grown across those 10 tumultuous rounds with Benn.

“How old are you?” he asks.

“Forty six.”

“Height?”

“Six-one.”

“Weight?”

“One-ninety.”

“You a boxer?”

“Not anymore.”

“Why’d you stop?”

“I was no good.”

Gerald recoils at this, grimacing, and his voice takes on a high pitch that I will come to recognize as a sign he is upset.

“Lisa! Why’d you let him say he’s no good?” he asks of his sister and full-time carer, with whom he shares this home in Freeport, Illinois. “Don’t let him say that!”

Lisa tells me later that Gerald rarely feels sorry for himself – such is the nature of his injury that he doesn’t really know that he is injured – but hates to hear of others feeling down.

“If you cry about what happened to him, he’ll hug you,” she says.

And while my abiding impressions from spending a day with Gerald McClellan can hardly be called feelgood, it is still surprising that the emotions it stirs are, for the most part, not negative ones. There had been trepidation about meeting a badly brain-damaged person and not knowing how they would act, or what I should say and do. I had expected to be distressed by seeing the condition in which he was in and the suffering he endured. And I had dwelled on the personal torment of being confronted by the despicable toll exacted by a fight I had enjoyed watching, by the ghastly cost of an outcome I had cheered for, and by the neverending nature of a plight that I had essentially ignored that night, when the image, televised into millions of homes, of Gerald being stretchered out of the ring was deliberately put to the back of my mind so I could continue drinking and celebrating with my friends.

There are, naturally, difficult moments during this day. Gerald’s physical condition is decrepit; he can’t stand or walk without support. There are outbursts, there is confusion, there is unintelligible rambling, and his short-term memory is minimal, meaning the same conversations can be had dozens of times. Even so, our interactions are rewarding. Gerald smiles and laughs easily. He is tactile, he wants to talk, he wants to know about me and where I’m from, he is pleased by the small gains of meeting a new person, and he appreciates the attention and recognition.

After a couple of hours, my name sticks. “Oliver,” he begins, no longer mistaking me for Steven. “Favourite sport?”

“Boxing.”

“Boxing! You know me?”

“Of course I know you; you’re the champ.”

“How you know me?”

“I saw you fight.”

“I win?”

“You sure did. You beat John Mugabi in London.”

“I knocked that motherfucker out!”

Another huge grin, another celebratory air-punch, and then a reset.

“Oliver. How old are you?”

“Forty six.”

“Married?”

“Yeah.”

“Kids?”

“Yeah, I’ve got one son.”

“He spar?”

“No, he’s just two years old.”

Gerald laughs – “I thought he was grown!” – and then resets.

“Oliver. How old are you?”

“Forty six.”

Variations of this conversation go round and round. He also tells me many times his idol is Tommy Hearns and asks if ‘Hitman’ is still fighting. When told he isn’t, Gerald asks why, and when told it’s because his idol is too old, he is taken by surprise. He refuses to believe that Hearns is 65, that Sugar Ray Leonard is 67, that Don King is 92, that his own father is 84, or that his sister Lisa is 55, even though she tells him this herself.

“He thinks he’s still 27,” says Lisa, which was his age when he fought Benn, and when time stopped. Mercifully, he remembers nothing of the Benn fight.

What was he like before his injury?

“Honestly? He was an asshole,” says Lisa. “Well, he was very good to people in that he was very generous with money. But I mean he was very, very serious. We didn’t really get along. Out of all the siblings [two boys and three girls], he and I were the least close.”

So, why did Lisa inherit the duty of caring for Gerald?

“I ask myself that every damn day,” she sighs. “I was in college training to be a nurse. I was going to take a job in Florida, but I came home to take care of Gerald.

“He had a girlfriend at the time and they had a child that was six months old when he got hurt, but she was soon gone. Initially, us three sisters shared the duty, but Sandra developed health issues of her own and Stacey stepped away for personal reasons.”

On top of that, their mother died in an accident in 1999, and their father had moved to Mississippi years earlier. Lisa refused to send Gerald to a nursing home, so chose to care for him on her own, in the house he had bought after winning the championship.

And what a marvelous job she does of that. If they were the “least close” siblings before, their love for one another is obvious now; a bond forged over 29 years in which almost every hour has been spent together, with any number of hopes and disappointments, episodes of medical and emotional turbulence, and the necessary intimacies of helping a person who relies on another for their every need: Lisa cooks for Gerald, bathes him, dresses him, helps him use the toilet, physically supports a man who now weighs more than 200lbs when he needs to move and walk, and gives him his medicine.

Recently, this medicine regimen has been added to, with a side-effect being the return of a desire for a kind of intimacy that not even Lisa can provide.

Gerald’s medicine cabinet is as full as you’d imagine. There are steroids, proteins, peptides, soporifics, vitamins and supplements. He has also had stem cell therapy and is currently on the Millennium Brain Rescue protocol, a hormone course aimed at improving deficits in attention, memory and emotion characteristic of traumatic brain injuries. This includes daily injections of testosterone, which are aimed at improving executive brain function but have also caused the resurrection of something long dormant: Gerald’s sex drive.

“Oh, boy,” says Lisa, rolling her eyes. “The beast has woken up. Sometimes it’s all he talks about: ‘Man, I need to make love! I haven’t made love in years!’”

There’s no outlet for that, and Lisa dismisses the obvious one. “Our dad said we can take him to someone who can help him out. I said, ‘a prostitute? Not on my watch!’ First of all, she might take advantage of him. Second, he might do something inappropriate she’s not expecting. Gerald can sometimes get aggressive. And if she’s dirty and they don’t use protection, do I need him catching something on top of all his other problems? So, I told Dad no, and he said ‘you can’t tell me what I can’t do for my son’. I told him next time he comes to visit, he can check straight in to the hotel, because he’s not staying here. We haven’t spoken since.”

There have been other, less problematic, gains too. Lisa says under the Millennium protocol, Gerald’s emotional state is more stable. He has fewer mood swings, he manages frustration better, and can concentrate for longer. His short-term memory is improving. “See? He already remembers you. Before, it took days of repeated contact for him to remember someone new,” she says. And I also see for myself evidence of another cause for optimism – maybe, just maybe, he is beginning to regain some level of eyesight.

I return to Gerald while Lisa starts to cook dinner. To tide him over, she gives him a bag of M&Ms. As we go back over the same conversations we had earlier, Gerald starts eating the M&Ms and then offers me the bag. I shake out a modest amount and he suddenly shouts: “Lisa! He only took three!”

Lisa comes back to the living room. “How many did you take?” she asks, and I show her my open palm with three M&Ms in it.

“You hurt my feelings,” says Gerald. I apologize, and he tells me it’s OK, hugs me and passes me the bag again. I take a more substantial amount and hand back the bag. “Keep it,” he says, so I do.

Later, Lisa marvels at this little moment. “How did he know you only took three? All tests show he’s still completely blind. He’s pretty sharp in other ways, like he can work out where you are based on sounds, or if I’m smoking a cigarette he can smell it and know where I am. But how could he know exactly how many M&Ms you took?

“There was another time when he hit me in the head with a shoe. He threw it from his chair while I was napping on the sofa and it hit me right in the head, right on target. I was asleep at the time, so I wasn’t smoking or making any sound. I woke up and thought we were being burgled, because who else would be hitting me in the head? But it wasn’t an accident, because then Gerald started laughing and he said, “I got that bitch!”

When it’s time to go, I sit next to Gerald, grab his hand one last time and start to say my goodbyes.

“Oliver? You’re leaving?”

“Yes, G-Man. It was a pleasure meeting you.”

“Come here.” He pulls me close, chest to chest, pushes the side of his head against mine, not to hear me better but in a show of affection, and hugs me tightly. “I love you, man.”

“I love you too, champ.”

My voice wobbles just a little as I’m taken aback by these actions and these words; by how much our simple exchanges have been valued by Gerald – and by me. I blink away a tear, hoping he won’t notice, because as Lisa had told me, and as I have seen, he is more upset by other people’s problems than his own.

Gerald McClellan, once one of the most ferocious, aggressive and intimidating fighting men the world has known, has been reduced to this basic level of human existence. And I’ve never met anyone quite so human.

Lisa breaks down a typical day in the McClellan household

MORNING

“I let Gerald sleep until he wakes up on his own, unless he has an appointment. This will be 8-9am if he’s had a good night; if the melatonin has worked and he’s slept an entire night. Without it, his brain won’t shut off and he can be awake for days.

“The first thing he does is he has a cup of coffee while I run his bath. He can sit in the bath unaided and he can brush his teeth on his own. After his bath, I make his breakfast. He used to be happy with Fruity Pebbles; that was his breakfast for 26 years. Now he wants a hot breakfast every day, usually three breakfast muffins and some hash browns, with juice.

“He spends most of his time in his chair in the living room. After breakfast, I sit down with him for an hour every day and just have a conversation. I ask him how he’s doing and usually he’ll say ‘I’m doing great’. We talk about various subjects; a lot of the time they’re subjects he chooses.”