ON THESE pages I once mentioned seeing Jackie Turpin working on Britain’s last boxing booth back in 1977. I consider myself very fortunate to have stepped into a boxing booth to watch some live fisticuffs, as this part of the game, so important in its day, has now gone forever.

The booth belonged to Ron Taylor, a Welshman born in 1910, who spent his working life travelling up and down the highways and bye-ways of the country with his booth, setting up in villages, towns and cities from Penzance to Scotland, with a small retinue of boxers who were willing to challenge all-comers for a few quid a week.

Fortunately, my good friend John Jarrett was also there that year and he interviewed Ron for a feature which ran in BN on July 8 1977. Ron told him that “The booths have been in my family since 1880, but I’ll be the last. You just can’t get the boys today, and it gets tougher every year. But I’ll carry on trying as long as I can, it’s in my blood.” Ron battled on for another 20-odd years and he finally passed away, in his late nineties, in 2006.

The heyday of the booths was, of course, before the war. Men like Jimmy Wilde, Freddie Mills, Benny Lynch and Tommy Farr learnt their trade on them, and there were more than fifty booths travelling around the country during that time. After the war everything changed. The Board of Control decided, in 1947, to ban licensed boxers from taking part in booth fights. This resolution proved to be very unpopular, especially with the editor of BN, who commented that “For years it has been generally recognised that the boxing booth has been the cradle of British boxing and has been the means of providing novices with their early experience and matured boxers with intensive training for big contests. Now that the authority has officially wiped out this source of supply, we would like to ask what it has to offer in its place. One can visualise that in future the booth will have to find its own youngsters and that it will become the last hope of good ‘has-beens’, more’s the pity.”

The Board felt that the booths were being run in direct competition to licensed promoters, using the same boxers, and that this was unfair to their licence-holders. The booths never fully recovered from this set-back, and men like Ron Taylor became a rarity. Jackie Turpin had no licence at the time that John and I saw him in 1977 as he had fought his last professional contest in 1975. He was one of the “has-beens” that the BN editor was talking about 30 years previously.

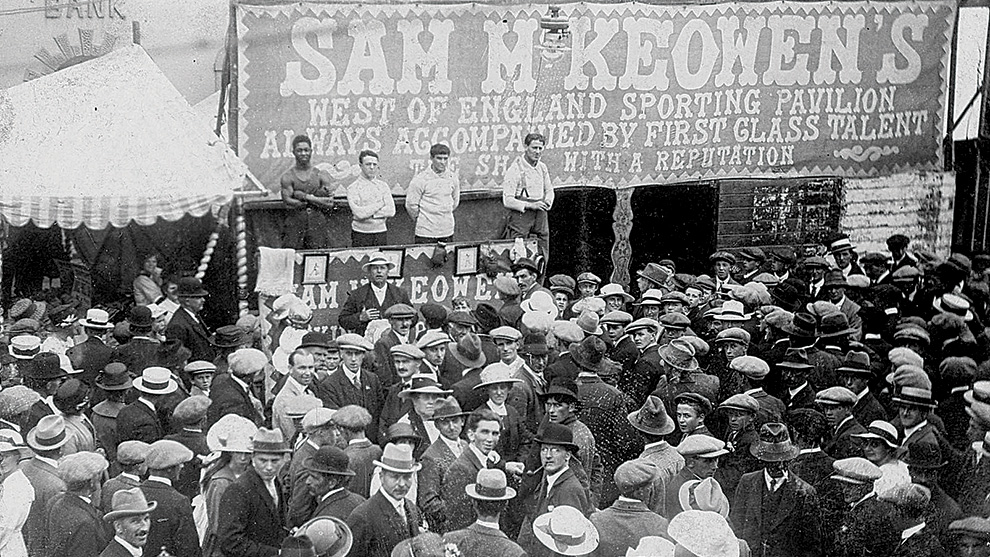

In the accompanying photograph, of Sam McKeown’s booth back in the late 1920s, one can sense just how popular these attractions were. McKeown, an ex-fighter himself, plied his trade around the fairgrounds of the South-West and amongst the four boxers on display, I am reasonably sure that that is Dixie Brown on the left. I have no idea who the other three are, but they will be leading professionals from the region. Dixie boxed between 1914 and 1944, winning 44 of his 103 contests, and he was typical of the sort of man you could run up against if you fancied your chances of surviving three 90-second rounds on the booths. Dixie probably faced around 10 or 15 local ‘hard-men’ every week and few of them saw the ‘fiver’ that they were trying to win by lasting the course. From Dixie’s perspective, his combined purses from around 15 contests a year could be enhanced by spending four months in the summer travelling around the area with Mr McKeown. He would have had many adventures on the open road, many memories, and many hard scraps with the local tough guys. Happy days!