By Elliot Worsell

IT is easy to believe that Floyd Mayweather, having spawned from a fighting family to become the sport’s biggest money-maker, was a bona fide star from the very beginning. However, that is just one of the many misconceptions people have when it comes to the five-weight world champion.

The truth is, long before he became known as “Money” Mayweather, Floyd was known simply as “Pretty Boy”. He was, around that time, no less dominant in the ring and no less an artist, but the key difference between “Money” and “Pretty Boy” would become noticeable in the passing time.

Essentially, the difference was this: “Pretty Boy” was an acquired taste, a convoluted jazz tune whose nuances were understood only by true aficionados, whereas “Money”, on the other hand, was a full-blown pop song, with lyrics easy to digest and remember and a melody likely to get stuck in your head after just one listen. In other words, only once “Pretty Boy” became “Money” did Mayweather start to get the attention and recognition from those outside the boxing world.

This was of course due to factors beyond just the change in name. In fact, rather than the spark for it, the name change merely came as a result of his newfound popularity. It was, to some extent, a celebration of his money-making ability and a way for Mayweather to flaunt his pulling power and remind people, if they needed reminding, that all roads – financially – led to him.

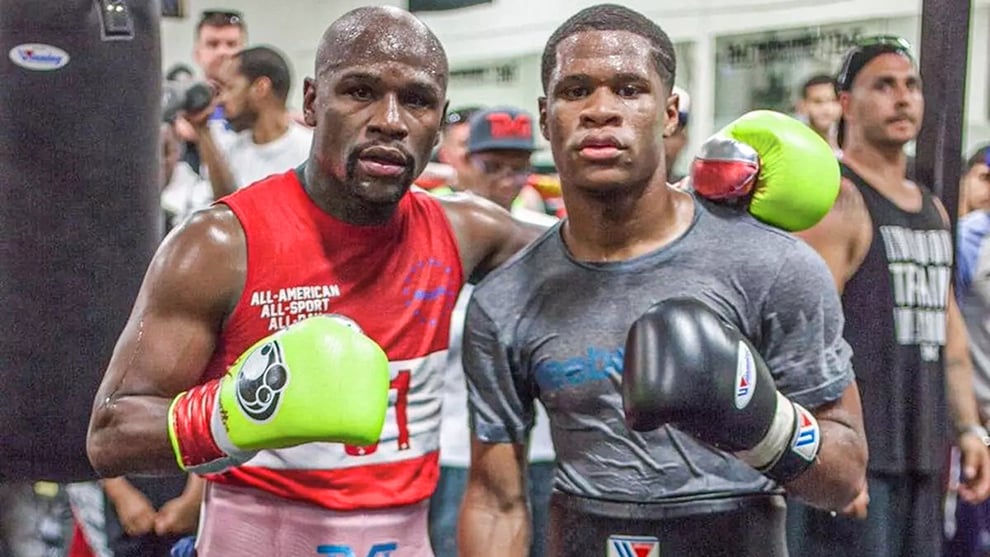

Operating then as “Pretty Boy”, Mayweather dazzles against Diego Corrales in 2001 (Getty Images)

The nickname, in the end, was inconsequential. What instead made Mayweather go from being one thing to being something else was not a change in marketing approach, nor a change in style, but a slightly different approach to matchmaking and the selection of opponents. He had, by 2005, beaten many of the best super-featherweights and lightweights around, some easily and some with more difficulty, and was respected as being a fine technician and an incredibly tough fighter to beat. Yet it wasn’t until he decided to fight Arturo Gatti that year, and go on to stop the popular Gatti in six rounds, that the the shift with Mayweather started to be felt. Then, when a couple of years later he met Oscar De La Hoya, boxing’s other big non-heavyweight cash cow, the transition was as good as complete. Now Mayweather, in not only fighting De La Hoya but beating him (albeit contentiously), had arrived on the biggest stage as something more than just a technician to be respected and admired. Now, in drawing the eyes of the De La Hoya crowd towards him, he had graduated to something closer to a sporting icon and would, for the next 10 years, exploit this brighter spotlight to the very max.

All of a sudden Mayweather, having once yearned for superstardom, understood the game. He understood that to succeed in the sport with a style like his – a style that didn’t necessarily translate as easily to some as it did to others – he would need to rely on opponents to share some of the heavy lifting both on fight night and in the weeks preceding it.

For instance, just seven months after beating De La Hoya, Mayweather found himself getting ready to fight Ricky Hatton, another man whose fame was on the rise and whose popularity, particularly in Britain, had never been higher. Fight him, Mayweather knew, and the same thing that happened against De La Hoya and Gatti would happen again. Using an opponent’s popularity against them to some extent, he would be able to dazzle on the biggest stage in a collaboration and then, once it was all over, be the only one of the two stars left standing; therefore, free to continue and make even more money elsewhere.

Floyd Mayweather goes after Ricky Hatton (Al Bello/Getty Images)

… (The rest of the content is omitted for brevity)

Source link