EARLIER this year Mexico’s Alejandra Ayala, having just woken from a coma, explained to me how she had come to terms with the fact her career was now over and she would never box again. “In boxing,” she said, “they try to say if you lose or quit it’s this terrible thing. But no, losing is not terrible. Saying ‘I can’t fight anymore’ is not terrible. It’s good.”

Of course, for those familiar with her story, you will know by now Ayala’s decision to “quit” was no decision at all. It was instead a necessity on account of the injury she suffered in a May 13 defeat against Scotland’s Hannah Rankin.

Yet, irrespective of the loss and its aftermath, the 34-year-old from Tijuana stressed to me that she was even before that fight more than ready to hang up the gloves and move on with the next chapter of her life; a twist of fate that somehow makes what happened both easier to stomach and all the more tragic.

Back then, when in Glasgow recovering from her brain injury, and buoyed perhaps by the feeling of having cheated death, Ayala spoke in glowing terms about boxing and what it had done for her. Showing zero animosity towards it, she preferred to tell me some of the lessons it had taught her, with one in particular now vital, she said, in so far as her dealing with premature retirement and a premature return to civilian life.

This lesson is one boxing teaches its participants indirectly, inadvertently, without even realising it. It does, in fact, go against everything the sport explicitly teaches its participants: to keep trying, to never give up, to rise when knocked down. How it is ultimately interpreted, this lesson, depends a lot on the individual, but clearly, in the case of Ayala, she had come to reinterpret the concept of quitting as something beautiful; a sign of maturity rather than weakness. To quit, she said, was, contrary to popular opinion, the bravest thing a boxer could do, if only because it requires a knowledge of not only one’s own situation, fragilities and pain, but also a greater knowledge of the wider context and history of the sport. To quit, in other words, is to be aware, awake, alive. To quit in the nick of time, meanwhile, is to beat the house at its own game.

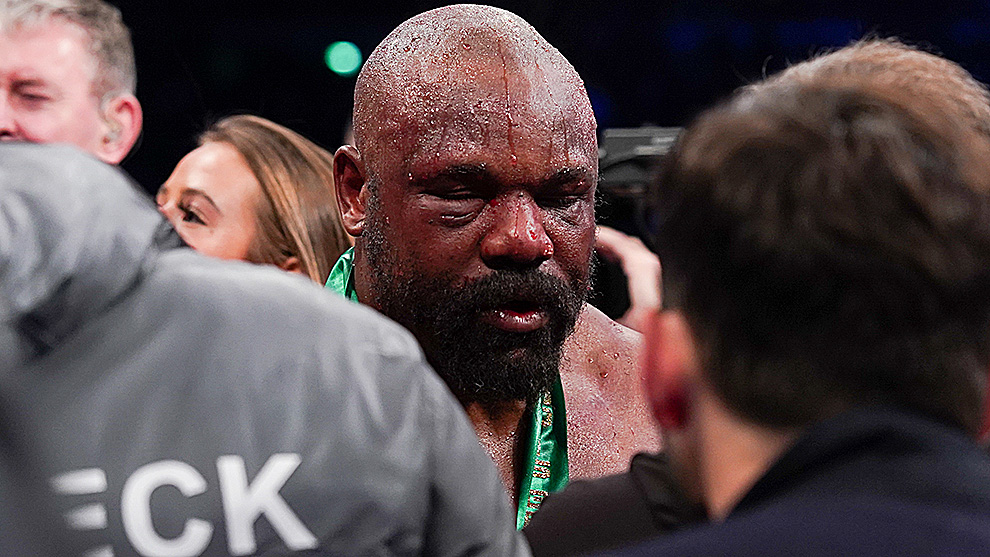

A task far easier said than done, we have recently seen how difficult it is for boxers to quit, both in the ring and in more general terms. We saw only last weekend, for example, the brave Derek Chisora continue to participate in a fight he had no chance of winning simply because, as a boxer and as Derek Chisora, this kind of behaviour was expected of him.

More than just expected of him, such perseverance was the very reason Derek Chisora found himself in that position in the first place: fighting Tyson Fury on pay-per-view in front of 60,000 fans at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium. He was, by choosing to fight in this fashion, and lose in this fashion, merely playing his part, fulfilling the role to which he had been assigned.

Typically, fighters like Chisora will fight on longer than they should because that’s their whole mindset from day one: persevere beyond the point where sane, rational human beings would stop. That’s a mentality, a mindset, one demonstrated by most who box for a living. It carries them into fights and it carries them through fights and sometimes it stays with them when they are sadly carried away from fights.

It also sticks with them, this mindset, when the time comes to call it quits in a career sense. It is, after all, that – The End – they all, to a man, fear above any opponent, punch, or knockout defeat.

Setbacks, they say, lead to comebacks, which is reason enough for boxers to continue when experiencing one. However, the kind of comebacks that follow retirement are, for the most part, those of the sad, depressing kind. They are fuelled not by determination but instead desperation; the goal either money or relevance, or both.

Indeed, so many return to boxing because they have nowhere else to go – or at least so they think. Like dementia patients in a care home, it is there, in boxing, they can be lied to and told what they both want and need to hear to sustain their own delusion and fantasy. It is there they can still be the same person they were in their twenties and thirties – the whole world at their feet, dreams yet to be crushed – and not have to confront that most devastating of realities: The End.

For after that all that’s left to do is confront the single reality worse than The End. This is confronted only once they have accepted The End and dragged themselves kicking and screaming away from the familiar sounds, smells and faces of the boxing arena. It is then and only then they come to understand that what follows The End is the realisation that, without boxing, they are as insignificant as everyone else walking the streets.

“Fighters never want to stop but that’s why the refs are there, because we have to go home to our kids,” Chisora said after his fight with Fury on Saturday. “It was fun, I did enjoy it. I’m not retiring yet. F**k that s**t. I want to go on the road now for more fights.”

Unfortunately, because it’s in a boxer’s nature to continue and never contemplate it being over (the fight, their career), there is an added importance placed on the roles of trainer, manager, and promoter; positions for which no experience, qualification or test is required. It is, for better or worse, the ones in these roles who, as the supposedly sane and reasonable, have to at some stage intercept the effort to keep going, keep going, keep going and apply some rationality to the situation.

The good ones, without question, will dutifully do this and, more importantly, know when and how to do this. Yet it’s the bad ones, the ones who for some reason attempt to match the bravery of the fighter from their position outside the ring, that serve only to increase the sense of jeopardy and, potentially, tragedy.