AT THE time, as the Seventies rolled into the Eighties, it was considered an experiment that failed. A career that lasted a mere three months; one that ran its course after one of the most anticipated debuts in boxing history. Simply put, the novelty wore off.

A decade before, there had been talk of 7ft 1ins basketball star Wilt Chamberlain challenging Muhammad Ali. The public was intrigued to the point the proposed match gained serious traction, but Chamberlain, at the last moment, had a change of heart. Ali’s barbs of “Timber”, when he saw Chamberlain, were said to play a role in waking the big man to the reality of what would transpire. Today it is ludicrous to think that Chamberlain, who had no boxing experience, could have even been semi-competitive but, back then, some people even wondered whether he could actually win. Unknowingly, that set the table for Ed “Too Tall” Jones to make his boxing debut on November 3, 1979 in Las Cruces, New Mexico.

That Jones was entering the ring at all captivated the sports world. As the number one pick in the 1974 NFL draft, Jones had gone on to have a stellar five years as a defensive end of the Dallas Cowboys, labelled as America’s team. Jones had helped lead them to three Super Bowls, winning one. He was paid well and a handsome new contract awaited him. Some thought he was using the threat of retiring from the NFL as a ploy to squeeze more money out of the Cowboys. After all, it made no sense, at least not on the surface, why one of the biggest stars of the sport who was in the prime of his career would leave it to become a novice in another. But, for Jones, the decision was not just easy, it was inevitable.

The public had always viewed Jones making life miserable for the opposing team. When the 6ft 9ins Jones was not sacking the quarterback, batting down his passes and snuffing out the attempted gains by running backs, he was wondering whether he could have enjoyed the same success inside of the ring.

“I grew up on a farm [in Jackson, Tennessee],” says Jones. “My dad was a great fight fan. I used to hang around the boxing gym with my friends when I was in high school. The guy in charge of the gym was named Rayford Collins who trained some very good fighters like Jackie Beard. He encouraged us to box. I had an amateur fight and knocked my opponent out in 36 seconds. It was in the newspaper.

“I was playing other sports in high school like basketball and baseball. I was very good. I had the same coach for both. When he read about me boxing he gave me an ultimatum, that if I continued I couldn’t be on any of the school teams.

“Boxing was my favorite sport, it was my dad’s favorite sport, but you have to understand how things are in a small town. Boxing was not nearly as popular as the others where I was from. Everyone in my hometown loved basketball and baseball. I would have been run out of town if I quit those sports and boxed. But I knew in my heart that one day I would box again.”

Ironically, Jones would attend college (Tennessee State) on a basketball scholarship, quitting the team after two years to concentrate on football. He became a two-time All American defensive lineman in college, leading to the Cowboys trading up in the draft to select him with the top pick.

Jones anchored the Cowboys’ ‘Doomsday Defense’, still considered one of the better defensive units in NFL history. “I had a four-year deal with an option for a fifth,” he explains. “After the fourth year I went to the Cowboys and told them I would play out the option but I did not tell them what I had planned. I then left after my fifth season.

“In the off season, the Cowboys called me and inquired why they hadn’t heard from my agent to negotiate a new contract. I then let them know about my plans to box. After they asked a second time, and got the same response, they knew I was serious and they could not change my mind. I made it clear to them that it was not about the money.

“The Cowboys respected my decision. Maybe they thought I would decide to play football for them again, I don’t know, but at the time I had no intention of ever coming back.

“My teammates were very supportive. We were very close. They were happy for me because I was doing what I wanted to, I was living my dream.

“When I played football I would go to the fights in the off season, and basically live in the boxing gym run by Rayford Collins. I knew that I could box and be successful if I put all my energy into it.”

At 28, Jones was a late bloomer to boxing, but his situation was far different from most. “Boxers are the best conditioned athletes in the world,” Too Tall opines, “but I was always in shape from my time with the Cowboys. I also had become good friends with Ken Norton and Larry Holmes who I could have potentially fought down the line, but both were extremely supportive. I met with Norton, who had me come to his training camp in California before he boxed Earnie Shavers. I remember the great advice he gave me, that I should keep the big entourage out of my career and my inner circle tight. Holmes showed up at a press conference before one of my matches because he wanted to show his support.”

Jones, with the help of his agent Don Cronson, settled on Dave Wolf to manage his boxing career and Murphy Griffith, the Uncle of Emile Griffith to train him.

Gina Andriolo is the current event coordinator of the Boxing Writers Association of America. At the time she was engaged to Wolf and was helping with the promotion and marketing of Jones. “The provision was that Too Tall would have to move to New York, to train,” says Andriolo. “He got himself an apartment off Central Park West, near the Museum of Natural History. I remember him as a very quiet individual who took boxing seriously. He worked out at the Times Square Gym on 42nd Street under Murphy Griffith, who had a military background and pushed him hard. Everything Too Tall wore had to be custom made; the trunks, robe and shoes. He was a very big man.”

Shortly after Jones came on board, Wolf and Griffith told him about an amateur boxer they were trying to sign. They enlisted Too Tall’s help. Being a famous NFL star could only help during the recruiting process. “We all went to Youngstown, Ohio to recruit [Ray] ‘Boom Boom’ Mancini,” says Jones. “We met his parents and friends. Murph and Dave both said his style was much better suited for the pros than the amateurs.

“Boom Boom’s mother was nervous about him going to New York, and where he would stay. When Murph offered to allow Boom Boom to sleep on his couch [in his small apartment on the upper west side of Manhattan], a deal was struck.”

Mancini and Jones were now stablemates. In a sense he became Too Tall’s new teammate, filling in a void that was missing from no longer playing for the Cowboys.

“Because of our age difference [10 years], we were not that close, but Boom Boom was someone I liked a great deal and had tremendous respect for,” says Jones. “I knew the bond he had with his father. I never met anyone in my life who worked harder than he did.”

Ed “Too Tall” Jones alongside Larry Holmes, Michael Spinks and Ray Mercer

In most circles Jones’ foray into boxing is ridiculed. That he won all six of his contests, five by stoppage, is considered much more the result of meticulous matchmaking than it is any ability he possessed. “Nonsense,” says Mancini, who boxed on the undercard of five of Jones’ fights, only missing the first one when he had to pull out due to illness. “Too Tall was a legitimate fighter who trained really hard and lived the life of a fighter. His opponents were credible for a fighter first starting out. They were no different than what a fighter coming out of the Olympics would face.

“I did roadwork with Too Tall and watched him in the gym. He had a jab that would KO guys. He punched so hard that you could feel the building shake. And when Too Tall sparred it was against real fighters. He was an inspiration to me when I saw he could afford a nice apartment. He deserved it.”

There is no film footage available from Jones’ time in the ring that can be found on YouTube. Being that CBS television in the United States broadcast all of his fights nationally, it is a mystery what has become of them. This writer reached out to David Dinkins Jnr, the executive producer for the Showtime Network which is affiliated with CBS. The hope was that Dinkins, who started working at CBS shortly after Jones retired, would shed some light on why the matches are not available to the public. But understandably he had no answers and did not know who would. Decades have passed, people have moved on. It is not exactly fight footage that is in demand like Harry Greb’s.

The lack of visual coverage adds to the mystique of Jones. It was that mystique which made his professional debut one of the most anticipated in boxing history. So much so that the $72,500 Jones earned for his opening bout was then largest purse ever given to a debutant. To put it into perspective, Sugar Ray Leonard, America’s darling by virtue of winning a gold medal in the 1976 Olympics in Montreal, had been paid $40,000 for his debut three years prior.

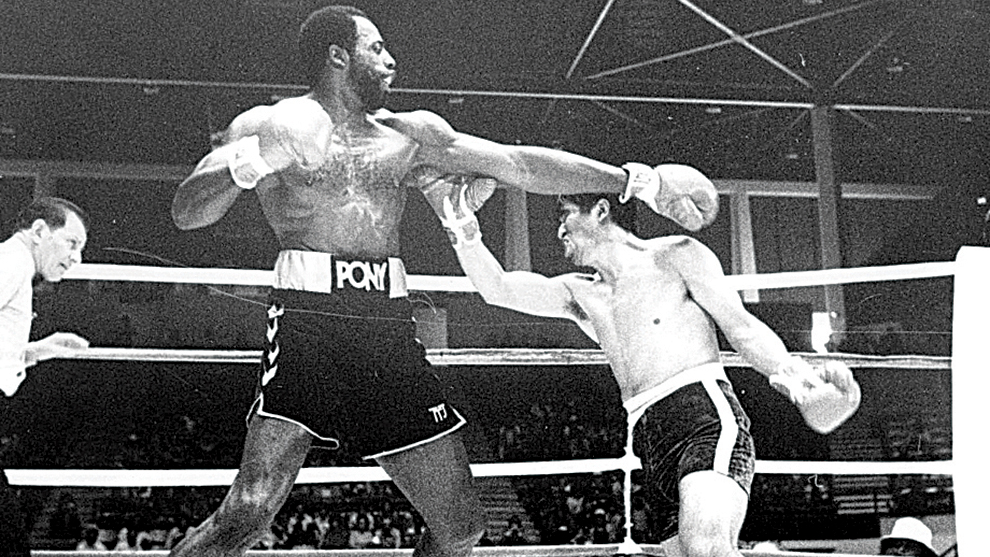

First impressions are usually vital. There might be no rebounding from a bad one. For Jones there wasn’t. Of his six fights, one stands out; his pro debut against Abraham Yaqui Menenses. The Mexican was giving away six inches and 50lbs. He entered the ring with a 5-6 (5) record. Physically, at least, it looked like a mismatch.

An impressive knockout by Too Tall would have whet fans’ appetite going forward, but he barely survived and won a majority six-round decision by scores of 57-57, 57-56, and 58-55.

In the last round, a left hook dropped Jones who was then flagrantly hit while down. A disqualification would have been justified, but the referee Buddy Basilico later admitted to underestimating the severity of the foul blow. Jones struggled to his feet before the 10 count and, prematurely, Meneses charged at him. While this was going on, Griffith was on the ring apron allegedly attempting to administer smelling salts to Jones. In any event it was close to a half-minute from the time Too Tall was dropped to when the action officially resumed. The break helped him survive to the final bell.

Jones’ version is somewhat different. “I was not knocked down, I slipped and he hit me while I was getting up. It threw my equilibrium off. We wanted a guy to fight. Yaqui ran. I had trained for a different type of fight.”

Although the decision in Jones’ favour was fair, to the public his limitations were exposed. In reality, Jones was nothing more than a novice who needed time to develop, but the television exposure coupled with the huge paydays made it imperative he perform at a high level.

Jones was back in the ring 10 days later in Phoenix, against Lee Holloman, owner of a 1-15-2 record. There was no drama as Jones grinded the Dallas heavyweight down, stopping him in the final round of their six. “He was an unorthodox fighter,” Jones recalled. I was trying to grow as a fighter. I knew it would take time.”

Jones’ activity level is to be admired. Before the month was out he fought yet again, this time in Washington DC, against Mexican Herman Montes, a veteran with an 18-12 record. Jones did the business inside the scheduled six, stopping Montes at 41 seconds of the opening round. An impressive accomplishment considering that Duane Bobick, a genuine contender, needed three rounds to dispatch of Montes earlier in the year. At the time, the big man felt that was a breakthrough for him. “After the match my sparring partners were telling me how much I had been improving.”

Too Tall’s inevitable homecoming occurred in his fourth match when he returned to Dallas, to face Phoenix heavyweight Jim Wallace, 2-3 (2). It was his only opponent out of the six who outweighed him, even if it was just by two pounds (246 to 248). Jones’ weight ranged from 243 – 255 ½lbs, for his six fights. When he played football it was more.

“During the week my team [Cowboys] showed up to watch me train. I told my people to get them as many tickets to the fight as they want and that they could bring family and friends. Well, they got me good. Some of my teammates sold their extra tickets and pocketed the money,” Jones recalls.

“Before the fight Muhammad Ali came up to me and said don’t duck punches, slip punches. It was good advice that I listened to.”

Jones stopped Wallace with one second left in the second round, but labels him the toughest man he fought. “He could punch really hard,” says Jones. “I felt the breeze from his punches when he missed.”

Too Tall was boxing so frequently and always at a different venue it felt like he was on tour.

Fight five came the following month against Tennessee heavyweight, Billy Joe Thomas, in Indianapolis. Jones’ education continued as he gained a fourth round stoppage. He says he remembers nothing about the fight. Thomas was winless in four matches, losing three of them inside the distance but he would subsequently last into the fifth round with Earnie Shavers and go seven with Mike Weaver.

A mere four days after disposing of Thomas, Too Tall was back in the ring against a San Antonio boxer named Rocky Gonzalez who was making his debut. Gonzalez would never box again after being stretched by Too Tall in one round. “I caught him with a good punch early,” says Jones. “I was shocked it ended that quickly. I never went into a fight thinking I would knock an opponent out in the first round. I knew it might be my last fight.” And it was. Shortly after Jones announced he was returning to play for the Cowboys.

Feeling that the mystique of seeing Jones in the ring had worn off, CBS made the decision not to telecast any more of his matches. Some surmised that without the television revenue, Jones’ paydays in boxing would have been reduced substantially making it not financially profitable for him to carry on. Jones dismisses that thought. “That is the furthest thing from the truth. I was making more money off of my different contracts from endorsement deals than I was from the Cowboys.”

The most obvious thought is that, unlike football, Jones’ ultimate potential in boxing was limited. His return to football was inevitable in the minds of many after he gave boxing a serious try. “I knew it would be difficult,” Jones says of his abbreviated career, “but I intended to be in it for the long haul. The money did not mean a thing to me. The plan was to box guys in the top 20 as soon as I was ready.”

So why did Jones, now 71 and residing in Dallas, leave the sport that he professes to love more than any other? “It is personal”, he says. “Someday I will tell the real reason.”

Mancini feels he already knows. “Too Tall had physical limitations. His hands were really bad. Griff had to put extra padding on his hands to protect them. A fighter with really bad hands is at a severe handicap. Had he not had the hand problems there is no telling how far he might have gone.

“I can assure you that Too Tall wanted so badly to succeed. His potential was unlimited, but realistically I am not sure if he had the agility to have gone to the top. He certainly had it in football, but boxing is different. We will never know, but to me his time in boxing was a success.”

This much we do know: Boxing made Jones an even better football player when he returned. In his first three years back he made the pro bowl team, the ultimate individual honour an active player could receive. “Boxing made being a Dallas Cowboy fun again,” says Jones. “I loved going to practice, studying game film and everything else about football because I was able to live my dream of being a boxer. I felt then and still do that boxing is the greatest sport in the world.

“I don’t care about the critics, not one bit, I really don’t.”

Jones starts to then list his accomplishments in football and talks about his 15-year career (1974-1989) that seem Hall of Fame worthy, yet he has not been enshrined in Canton, Ohio with the other greats of the gridiron. “People assume I’m in the pro football Hall of Fame, but I’m not. My friends get upset, but I never concern myself with it.”

Critics remain, but the positive legacy Jones left in boxing was apparent in 2008 when he served as the Grand Marshal of the parade during the Hall of Fame induction weekend in Canastota. “He interacted great with all the people. Our volunteers loved him,” said executive director Ed Brophy. “He was polite and accommodating to everyone. Because he loves boxing he understood and had respect for the achievements of the fighters there. We would love to have him come back.”

Too Tall Jones entered and left boxing on his own terms. There are not many other fighters who can say that.

Ed “Too Tall” Jones walks the red carpet at the 2018 So the World May Hear Awards Gala benefitting Starkey Hearing Foundation at the Saint Paul River Centre on July 15, 2018 in St. Paul, Minnesota (Adam Bettcher/Getty Images)