IT’S OFTEN assumed that every fighter starts out with the intention of becoming a world champion. But after beginning his professional career with a 6-6 slate, those intentions had to be fading fast for heavyweight Mike Weaver.

Enter Ken Norton, a future champion himself who Weaver trained with…well, whenever the Texas-born Californian decided to make his way to the gym.

“I worked with Ken Norton one day, and he told me, ‘Michael, you don’t come to the gym regularly for training and you don’t take it serious. If you come to the gym regularly and focus, you can make a lot of noise at heavyweight,’” recalled Weaver, who estimates that he only showed up one or two days a week to train. Despite this, whenever the phone rang with a fight offer, the then-23-year-old would answer.

“I had some ups and downs because I would fight anybody,” Weaver told Boxing News earlier this month. “One day I was getting ready to go to a party and I get a call. ‘Mike, can you fight tomorrow? The guy fell out. Will you take it?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I’ll take it.’ I drove up there the same night and went to the fight. It was crazy.”

Notice that there was no inquiry about the opponent he would be fighting, and that was Weaver’s M.O. in those early days after he left the U.S. Marine Corps and started boxing professionally. A star football and track and field athlete in high school, Weaver picked up boxing in the military, ultimately compiling a 23-3 amateur record before entering the punch for pay ranks in 1972. And in those early days, he fought four unbeaten opponents, including Duane Bobick, along with Duane’s brother Rodney. But it took that talk with Norton to convince him that maybe there was more to him in boxing than being an opponent.

“I never forgot what he said. It was around ’74 when I used to work with him. I took what he said, got me a manager who knew the business and cared about me. I told him what I wanted to do, and I started taking it seriously.”

Teaming up with manager Don Manuel in 1976, Weaver went 8-0 after the Duane Bobick loss in 1974, before a pair of losses to Stan Ward and Leroy Jones. Disappointed but not discouraged, Weaver faced Colombian contender Bernardo Mercado in October of 1978. At ringside was heavyweight champion Larry Holmes, who had just made the first successful defense of his crown against Alfredo Evangelista.

“Larry Holmes was there. As a matter of fact, he was the one who presented me with the trophy (as Nevada State heavyweight champion),” said Weaver, who stopped Mercado in five rounds. “The next thing I know, they asked me if I would fight Larry Holmes. I was like, ‘Yeah, right.’ I thought my manager was jiving. He said, ‘No, Larry Holmes wants to fight you.’ Once I found out it was serious, I told everybody, ‘I’m gonna fight Larry Holmes.’ They said, ‘He’s gonna beat you up, Mike.’”

Weaver laughs at the doubters who surrounded him back then, and he had an answer at the ready.

“I was confident. I wasn’t scared of Larry Holmes or nothing like that. I told people I’m gonna fight him. He might beat me, but he’s gonna know he’s been in a fight.”

Holmes was in a fight, and a few rounds in on June 22, 1979, at Madison Square Garden, the specter of an upset was in the air.

“I was hitting Larry Holmes and I was hurting him,” recalled Weaver. “But after five rounds, I was getting tired.”

Weaver wouldn’t back down, but his gas tank was draining with each passing frame. In the 11th, an uppercut finally dropped the challenger. A round later, Holmes had retained his title via TKO.

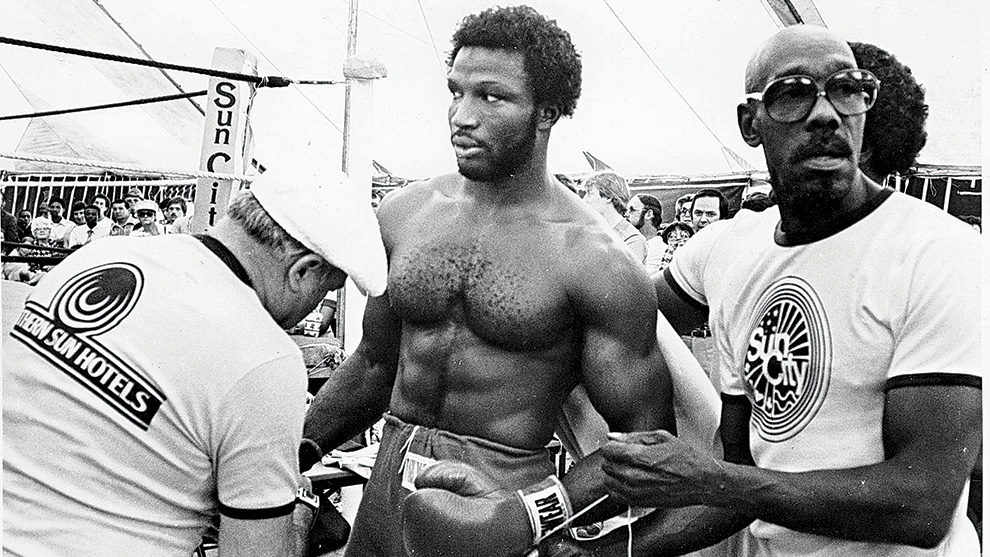

It was a tough loss for Weaver, but a win in many other ways, as the fighter now dubbed “Hercules” for his impressive physique, was a player on the world boxing scene, and two wins and nine months later, he would get a second crack at the crown, this time against unbeaten former U.S. Olympian John Tate.

Tate, who took the vacant WBA title in a bout with Gerrie Coetzee, was seemingly given a soft touch for his first defense in the 21-9 Weaver, and most of the boxing world assumed he would win handily, especially fighting in his hometown of Knoxville, Tennessee.

“I told everybody I was going to knock out Tate,” said Weaver. “And I believed it. I actually bet a couple people. One guy said, ‘How do you think you’re gonna do?’ I said, ‘I’m gonna win.’ ‘Wanna bet?’ We bet $500.”

Weaver laughs, but for 14 rounds, it looked like he was going to be out $500 as Tate built up an insurmountable lead. Entering the 15th, the Californian needed a knockout to win, and he was determined to get it. If he wasn’t, Manuel had some extra incentive for him.

“My manager Don said, ‘You told everybody you’re gonna beat Tate. If you don’t do it, don’t come back.’”

Weaver did it, with a single left hook felling Tate like a tree being chopped down. The soon-to-be ex-champion hit the deck face-first, essentially passing his belt to Mike Weaver on the way down.

“I was waiting all night to do it. He got caught with that left hook and he went down,” said Weaver, whose life had changed with one punch, whether he realised it at the time or not.

“I had a little bit more money,” he said. “I could buy more food to eat. (Laughs) I had a little money to get things I didn’t have. I got me a Corvette and stuff like that. But other than that, nothing changed.”

That went for his motivation, as well, because, if anything, getting the title made him more inspired to keep it.

“I still stayed hungry,” said Weaver. “I went to South Africa (to fight Coetzee) and that’s the hardest I trained. I was still motivated, and I trained even harder because I was champion, and I knew somebody wanted to take that from me. That championship belt on me sure looked good, so I trained hard.”

Mike Weaver at Hard Rock Live! in the Seminole Hard Rock Hotel Casino on September 5, 2015 in Hollywood, Florida. (Johnny Louis/FilmMagic)

Now 71, Weaver admits that outside of Tyson Fury, he couldn’t tell you who holds the belts at heavyweight, an indictment of the state of the game these days.

“I used to follow boxing all the time, and now I don’t know who the champion is. It’s just bad.”

Once derided, many believe that if the heavyweights of the 80s – Weaver, Holmes and their peers – were around today, they would not just be champions, but dominant ones at that. That’s fantasy matchmaking, but Weaver would like to think that’s true.

“I’d like to believe that if I was around today I’d be champion,” he said. “I think I’d do pretty good in this era, but who knows.”

And truth be told, even at 71, Weaver looks like he could go a few rounds in the ring if need be.

He laughs.

“Not to be bragging, but I’m in pretty good shape for 71 years old. I take care of myself.”

Twenty-two years ago, Weaver could do more than that, and as he traveled to Sun City in South Africa to face another favored foe in Coetzee, he had no doubt that he was going to retain his WBA title and come back home with the belt.

“I knew I was gonna beat Coetzee,” he said. “This guy has never been knocked down, never been off his feet. I’m gonna be the first one to do it. And that’s what I did.”Weaver had to eat some thunder to get there, though, most notable Coetzee’s fabled “bionic” right hand.

“He hit me with it in the eighth round and I thought I was on a merry-go-round,” laughed Weaver, who stopped Coetzee in the 13th round. A second successful title defense followed over James “Quick” Tillis, before two low points in his career against Michael Dokes.

In their first fight in December 1982, Weaver was the victim of one of the most bizarre stoppages in boxing history, as referee Joey Curtis halted the bout just 63 seconds in, with Weaver on the defensive, but seemingly not hurt.

“I was very pissed off,” said Weaver. “I remember a guy told me, ‘Watch out Michael, they’re gonna stop the fight early, the first chance they get.’ He told me, but I didn’t pay attention. But I was very pissed off.”

To this day, Weaver believes the fight wasn’t on the level, but he did get a rematch with Dokes six months later. This time, the bout was ruled a draw, which didn’t soothe the disillusionment Weaver now had for the sport.

“I was more pissed off then,” he said of the Dokes rematch. “It was a good fight, but I really thought I won it. I hit him the hardest, I backed him up, and I thought I won the fight, but they called it a draw. After that, I really started losing a little interest. I really didn’t trust the game no more.”

Weaver still had a name, though, and he still could fight, which meant there would be more opportunities, and in June of 1985, he got a shot at Pinklon Thomas’ WBC title. It was a chance at glory once more, but Weaver knew it was a losing battle before the opening bell even rang.

“When I fought Pinklon Thomas, I actually knew I wasn’t gonna beat Thomas,” he said. “You can tell when your legs are ready to go, and when I used to run, everything felt weak in training. No one knew it, but I knew it. So I said I’ll do the best I can, but I really didn’t think I could beat him. And that was it.”

The former champ hit the deck twice, and while the fight was dead even on the scorecards, at 1-42 of the eighth round, he had lost his last opportunity at a heavyweight title. He was 34 and continued to fight for another 15 years, with his final bout in 2000 a bizarre rematch with Holmes, one he certainly didn’t see coming.

“They came to me with that fight and I said, ‘I ain’t been in the gym over a year,’” said Weaver, who followed up that statement with a question. “‘How much am I getting?’ $50,000. ‘You add ten more I’ll take it.’”

Weaver got his $60,000 and was stopped in six rounds, ending his career at 49 with a record of 41-18-1 with 28 KOs. Many of those defeats came in the final years of his career, when he was still fearlessly taking on the likes of “Bonecrusher” Smith, “Razor” Ruddock, Bert Cooper and Lennox Lewis. And while he points to the Tate fight as his favorite, he then recalls a good night after the Thomas bout when he put a dent in the chin of Carl “The Truth” Williams in 1986.

“He actually told people he was gonna walk through me in one or two rounds,” said Weaver. “But he was right, it didn’t go two rounds. (Laughs) Someone told me, ‘You’re gonna knock him cold with a left hook.’ And that’s just what happened.”

Weaver smiles, content with a career well-fought. These days, he describes life as “Staying at home, bored to death because of the COVID,” but he hopes to get back out to the fights soon, because when he goes, he rightfully gets acknowledged for what he gave to the sport.

“People tell me, ‘You never gave up, you didn’t care who you fought, and you were always determined, and you never put nobody down,’” said Weaver. “They tell me that all the time and I think that’s wonderful.”