By Thomas Hauser

SIXTEEN years ago, an Iowa attorney named Adam Pollack founded Win By KO Publications. Pollack has worked as a trainer, referee, and ring judge. But his greatest contribution to boxing lies in a series of biographies he has written about boxing’s early gloved heavyweight champions.

“Publishers wanted to edit my books down and wouldn’t use the photos I wanted to use,” Pollack recalls. “I wanted total control over my books and how what I wrote was published, so I decided to do it myself. Then other writers started coming to me, asking if I’d publish their books.”

Win by KO has published 25 books to date; 11 by Pollack and 14 by other authors. All but one (a novel by VADA president Margaret Goodman) are non-fiction. Homicide Hank: The Life of Boxing Legend Henry Armstrong by Kenneth Bridgham is its latest offering. Armstrong is credited with a 1956 autobiography titled Gloves, Glory, and God. Other than that, Homicide Hank is the first book-length work written about a man who’s universally acclaimed as one of the greatest fighters who ever lived.

Armstrong was one of 13 children born into a sharecropping family in rural Mississippi sometime between 1909 and 1912. Named Henry Jackson Jnr at birth, he later took the last name of his trainer and friend, Harry Armstrong.

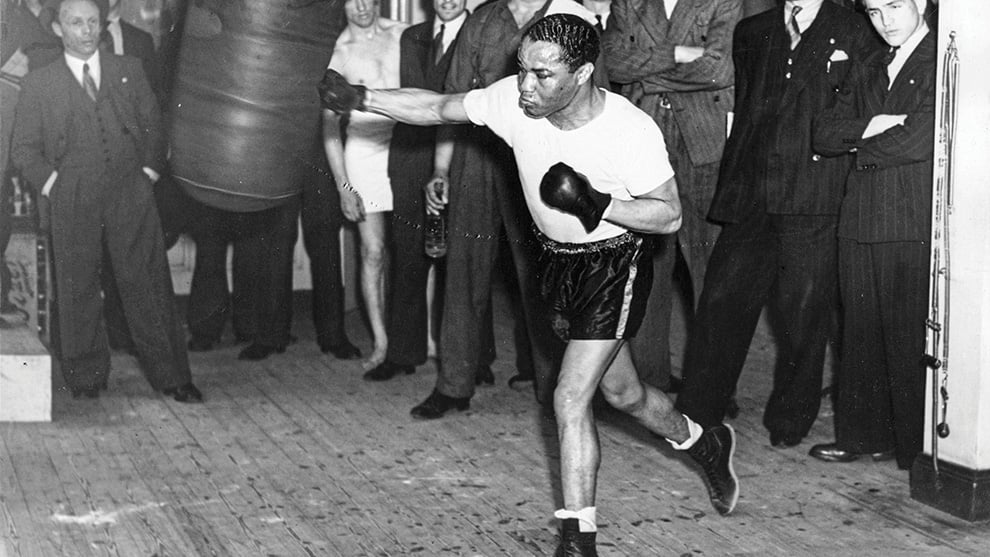

Fighting professionally from 1931 through 1945, Armstrong amassed a ring record of 147 wins, 21 losses, and 11 draws with 98 knockouts and 2 KOs by. At his peak, he held world championships simultaneously in three weight classes at a time when boxing had eight weight divisions and only one champion in each division. His accomplishments were almost beyond comprehension. He was “pound-for-pound” before the phrase was invented for Sugar Ray Robinson.

Armstrong fought 27 fights in 1937 and won all of them, 26 by knockout. He captured the featherweight crown that year by knocking out Petey Sarron. Then, over the next nine months, he added the welterweight championship with a lopsided decision over Barney Ross and annexed the lightweight title with a victory over Lew Ambers. For good measure, he fought 12 title fights in 1939 and won 11 of them. He went in tough again and again and was close to unbeatable in his prime.

He also became a cautionary tale. Most of the money Armstrong earned that he didn’t spend on gambling, cars, nightclubs, women, drinking, and expensive clothes was stolen by people he trusted. Even Joe Louis (a notorious spender) cautioned Henry, “Slow down. Nobody’s money goes as far as you stretch it.”

“He ought to be in some less wearing trade by now,” David Lardner wrote of Armstrong in 1944. ” But when he’s in the ring, he makes good money. And when he’s anywhere else, he loses it.”

“I fought hard and I lived just as hard,” Armstrong later acknowledged. “I drank like a demon and I gambled. If I didn’t chase women, it’s because I didn’t have to. They chased me.”

Late in life, Armstrong found God and became a preacher. Then dementia and other demons that too often torment fighters set in. He died in 1988.

Bridgham provides a nice framework for Armstrong’s story. “One of the challenges of writing about a professional boxer from the 1930s and 1940s,” he notes, “is conveying the sport’s importance in American culture. Children in the 1930s could have told you the reigning heavyweight champion’s name before they could identify the president of the United States.”

Drawing a distinction between boxing and baseball (America’s other national sport in that era), he writes, “For all its popularity, baseball was not integrated. It offered no example of Black men succeeding against white opposition.”

Other sociological insights regarding race are also on point.

“Jim Crow,” Bridgham states, “was more than just legal statutes and signs on water fountains reading ‘whites’ and ‘coloreds.’ It was more than just segregation of neighborhoods and schools. For the people who lived it, it was a code of daily behavior meant to reinforce Black people’s subjugation as second-class citizens in perpetuity . . . As far as the public was concerned, Henry Armstrong was a quiet smiling well-behaved Negro who could fight like hell, and they wanted nothing more from him.”

“Being a black celebrity during the Great Depression,” Bridgham continues, “was a tightrope walk. One had to be non-threatening, non-political, and reinforce white peoples’ beliefs about their own superiority, especially if one wanted to cross over to the more lucrative white audience. Black celebrities who crossed over to white approval and made good money were figures like Bojangles, Ethel Waters, Louis Armstrong, and Hattie McDaniel. All were talented individuals but their popularity largely rested on their willingness always to appear as though their only purpose for living was to entertain and that they never resented anything about their status as second-class citizens.”

Bridgham also draws a nice contrast between Joe Louis’s two fights against Max Schmeling.

Regarding Louis-Schmeling I (when the “invincible” Brown Bomber was knocked out in the 12th round), he writes, “The immediacy and far-reaching signal of radio had made Louis a new kind of Black hero. And his defeat brought an equally new kind of widespread sorrow. Lena Horne, who had broken down and wept along with the rest of her band during the fight, put it more simply. To her and her people, Joe was now ‘just another Negro getting beaten by a white man.’”

Bridgham then moves to Louis-Schmeling II (when Louis destroyed Schmeling in one round) and recounts, “Black people already regarded Louis as the living refutation of the hatred spewed forth daily over radios, in newspapers, in movies, and in books about their lives. With this new victory, Louis had sent this refutation worldwide. An estimated five hundred thousand people erupted in Harlem’s streets in ecstacy and many stayed there till sunrise. New York’s police chief told his men to back off, saying, ‘This is their night. Let them be happy.’ It was, reported Porter Roberts in the Pittsburgh Courier, ‘the greatest show of Negro unity America has ever seen.’”

And there are interesting nuggets of information interspersed throughout the book. For example, in 1964, Barney Ross appeared at trial as a character witness for Jacob Rubenstein (better known as Jack Ruby), an old friend who’d been charged with the murder of Lee Harvey Oswald (John F. Kennedy’s assassin).

But Homicide Hank isn’t without flaws. Bridgham writes that, early in his career, Cassius Clay was managed and trained by Archie Moore. No! Moore briefly trained Clay but never managed him. Boxing historian Peter Heller is inadvertently referred to at one point as “Joseph Heller.” And writing of the Great Depression, Bridgham states, “On October 29 [1929], Americans opened their newspapers to find headlines declaring the most significant stock market crash in the history of Wall Street, a staggering fall of fifteen thousand points.”

That fifteen-thousand number is troubling. The 1920s stock market peaked at $381.17 on September 3, 1929. On October 28, 1929, it dropped 12.82% ($38.33) to close at $260.64. The following day, it dropped another 11.73% ($30.57) to close at $260.64.

Errors like these can undermine confidence in the overall accuracy of a manuscript. And there are places where Homicide Hank blurs the lines between fact and fiction.

The details of Armstrong’s early life are shrouded in uncertainty. Bridgham writes evocatively of Armstrong’s childhood. But as I read, I had the nagging feeling that some of what I was reading was apocryphal rather than accurate.

Armstrong was a teller of tales. He gave different versions of events to different people. Bridgham relied heavily on the fighter’s autobiography. But as Adam Pollack said recently of fighter autobiographies, “For the fighters’ own personal feelings and certain insights into how they thought about things, those books are okay. But if you’re looking for accuracy, forget it. Most of the old autobiographies are self-serving and wildly inaccurate. And most of the time, these guys were talking years later off the top of their head. And they were hit in the head a lot.”

Further to this point; Bridgham writes that Armstrong would forever remember his grandmother’s stories of life in slavery and of “once seeing the Great Emancipator, Abraham Lincoln, with her own eyes as an enslaved girl in Alabama.”

However, Lincoln was never in Alabama. Yes, Armstrong’s autobiography recounted his grandmother telling him that story. But shouldn’t Bridgham tell readers that it wasn’t true?

That said; Homicide Hank gives readers a good look at a man who, in Bridgham’s words, “punched as though he were trying to rip open the air.” Grantland Rice likened Armstrong’s fighting style to “wildcats using machine guns as well as claws.” And Damon Runyon wrote, “A man would have to have an axe in there with Henry to make it even up. And he would have to be an expert with it.”

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His most recent book – The Universal Sport: Two Years Inside Boxing – was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism. In 2019, Hauser was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.