THERE is never a bad time to talk about world flyweight title fights and champions.

Sunny Edwards defends his title on Saturday at the traditional home of world flyweight champions, Wembley. There is something strangely old-fashioned about flyweight, a division that brings back memories of great nights and terrible endings. And a lot of action.

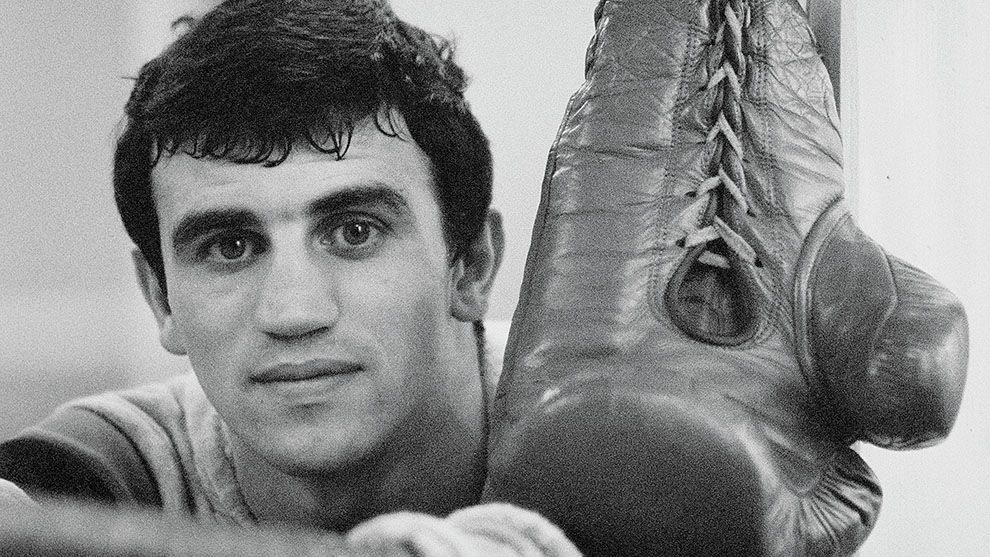

The one-time hero of every seat in that old building was Charlie Magri. He was known, rather bizarrely, as Champagne Charlie. He left enough of his blood and heart and guts on the canvas in the Wembley ring that there should by rights be a blue plaque on the wall outside. Charlie Bled Here, that type of thing.

This flyweight story is not about little Charlie at Wembley. There is a short drive necessary on the North Circular to get to Alexandra Palace. It’s 1985 and Magri is in the twilight of a career that we still don’t give him full credit for. He was the boxing prince of sold-out nights at the Empire Pool, to give Wembley its name from the time, and the Royal Albert Hall.

Magri delivered masterful and emotional nights, winning and losing titles in brawls; Magri could bang and be banged. A huge 23 of his thirty wins were by stoppage and every one of his five defeats came early. If you bought a ticket to see Magri fight, you would be out by about 9pm. Magri won and lost the WBC flyweight title there and won and lost in European title fights in that ancient ring. How about this: Magri won the British title in just his third fight, just forty-two days after his pro debut and the weigh-in was at the Odeon Cinema in Leicester Square. Magri was a real star, a bright-lights kid.

As a sign of Magri’s potential, look at this mad statistic. In 1974, Magri went to Kiev for the European under-21 championships. It was the third edition and the previous two had also been behind the Iron Curtain. Little Charlie reached the final, left with a silver. That came close to breaking a monopoly. There were 11 weights and Eastern European boxers had won all 22 of the previous gold medals; in Kiev this would be repeated, with the Soviets adding seven more to their remarkable haul of 11. Don’t despair at Bakhodir Jalolov fighting as a pro and then putting on a vest to win world amateur and Olympic gold, it is not new – the shamateur Eastern Bloc kids were doing it 50 years ago.

In 1985, Magri had won and lost his titles. His face was evidence of his sacrifices inside the boxing ring. He was still an attraction, still could fight. In February of that year, he fought for the WBC title for the last time. But it was not straight forward.

The opponent was Thailand’s Sot Chitalada. He had only fought eight times; he had lost a world title fight and knocked out five of the seven men he had beaten.

The fight was made in Charlie’s sports shop in Bethnal Green, and it is richly comic. And it is all true, honest.

Magri was still run and controlled by Terry Lawless and his partners in the legal cartel, including the promoter, Mickey Duff. However, Frank Warren, an upstart at the time, had an offer for Magri. A meeting was arranged at the shop and Magri’s manager and trainer, Lawless was there, as was Warren and his matchmaker, Ernie Fossey.

The offer was in the region of 40,000 pounds and that was Magri’s second-highest purse. Lawless sulked and refused to talk directly to Warren or Fossey. It was slapstick, but the deal was done. It was good money and there was no way the cartel was missing out on that cash.

“I had to ask Charlie to ask Terry and Terry had to tell Charlie to tell me,” said Warren. “It went on like that. Still, we got it across the line.”

I had the same thing once with Duff on the way back from a show in Basildon in about 1992. He had banned me, but we shared a lift. I swear, we talked the whole way with a man called Ron Boddy working as a translator for the lunacy. Duff eventually won a court settlement, and we started talking. It was only business, as he told me.

It is not the fight you remember. Magri hurt Chitalada in round two. It is a savage and short fight; Magri has a very nasty cut over his left eye. At the end of the fourth, Lawless pulls Magri out. It was a great stoppage. One judge had Chitalada in front, the other two had it a draw after four.

“I knew how good he was and then I caught him, I went for him – I had to have a go,” Magri said. He did catch him and that is always forgotten. Magri went and had a shoot-out with Chitalada. It was bold, it was stupid, it was brilliant – it was Charlie doing what Charlie always did. He would be a superstar today.

The real end for Charlie Magri and his life and fights at the Empire Pool, Wembley, was the following year. Duke McKenzie dropped and stopped him in the fifth. Amazingly, between the Chitalada and McKenzie fights, Magri went to Italy and won the European title. Magri was a forlorn figure that night at Wembley after McKenzie and needed an arm across his shoulders. The fans were not there for him, the long road to flyweight glory was over. In the broken dressing room that night a chilling exchange took place. It’s harsh, but true and captures our brutal sport.

Magri had a blood-stained towel over his head when Lawless sat down next to him. “You are going to have to get up off your arse and go out and get a real job now.” Wow, that is cold. As I said, there is never a bad time to share a flyweight tale.