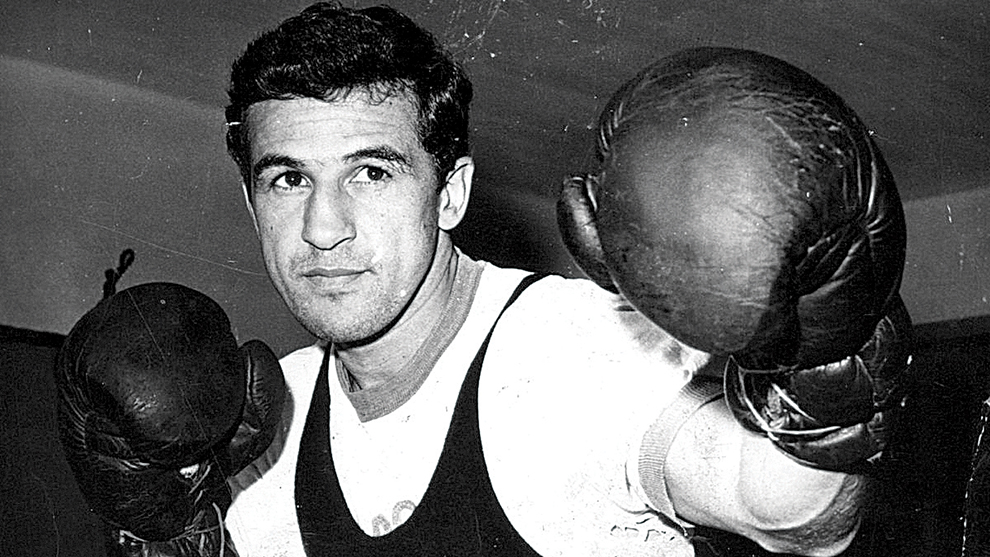

Daniel Herbert pays tribute to Brazil’s first world champion

EDER JOFRE, who died on October 2 aged 86, was for many the best bantamweight who ever lived. He was Brazil’s first world champion and remains its most celebrated boxer, matching skill with punching power to compile a formidable record in a time of strong competition.

The Sao Paulo man was world 118lbs king for the first half of the 1960s, winning a version of the title and then unifying before losing twice to Fighting Harada. Lack of motivation and weight-making woes made him retire – only to return and win a world belt up at featherweight in the early 1970s.

Agent Don Majeski, who has been involved in the sport since the 1960s, rated Jofre as the best bantamweight in history when interviewed by this publication.

And when BN produced its 100 Greatest Boxers of All Time work a decade ago, Jofre was ranked No. 28 overall and the highest bantamweight. (Next best was Ruben Olivares at No. 54).

The bare stats are startling. In 78 fights, the only man to ever beat him was Harada (in Jofre’s 51st and 53rd pro fights). He was held to a draw four times (twice by one man), but beat all three of those fighters in returns.

His powerfully built 5ft 4ins frame generated great power in either hand, with 50 of his 72 wins inside the distance. His first nine bantamweight title wins all came before the final bell.

And Jofre did not live in an era of avoiding dangerous challengers. He won bantamweight title fights in the USA, Venezuela, Japan, the Philippines and Colombia.

He was convinced he’d done enough to win the first fight against Harada, a former world champion at flyweight who after his bantam reign would go very close to becoming global ruler at featherweight (when being a three-weight world champion was extremely rare).

Jofre came from a family steeped in boxing. His father, grandfather and an uncle were all boxers, with father Jose opening a gym and training his son all through his career. Eder had his first amateur bout at nine and would become good enough to represent Brazil in the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, but defeat to Chile’s Claudio Barrientos in the quarter-finals prompted him to go pro.

He moved quickly, boxing a 10-rounder in only his third paid fight, and by 1960 ruled South America. When world bantam king Jose Becerra retired in August that year, the NBA (forerunner of the WBA) and EBU arranged eliminations to crown a successor.

In November 1960 Jofre knocked out Eloy Sanchez with a right cross in six to become champ for the NBA, but when France’s Alphonse Halimi – his EBU counterpart – refused to fight him, the Brazilian beat Italy’s Piero Rollo (KO 10) to earn Ring Magazine recognition.

In January 1962 any remaining confusion was cleared up when Belfast’s Johnny Caldwell, who had beaten beat Halimi, travelled to Sao Paulo and was hammered in 10 rounds by the brilliant Brazilian. Caldwell jabbed and moved but could not hold off the aggressive and powerful local.

Of his next five title fights, four were on the road – something Jofre put down to his nation being poor. He said, “When I was defending the title in Brazil I was not making enough money. When I fought in an opponent’s country I could usually make more.”

Gradually, his motivation waned as training became a chore and weight-making – never easy for him – took its toll. His luck eventually ran out in 1965 when Harada won a split decision in Nagoya that left Jofre fuming.

“Even the people in Japan thought I won,” he said. “Harada’s style was moving forward. He butted me and did a lot of holding.”

A Tokyo rematch a year later saw Harada win unanimously – and this time there was no argument, just Jofre’s mistake in coming in too light at 116lbs (2lbs inside the bantam limit).

He announced his retirement in January 1967 and if he’d never boxed again he would still have been one of the greats. Yet remarkably by August 1969, at 33, he was back in the ring as a featherweight, beating Rudy Corona in Sao Paulo.

He boxed steadily against good opposition but it was still a shock when in May 1973 he won a split decision over Spanish-based Cuban Jose Legra for the WBC 126lbs belt. He was then 37 years old.

He made one defence, a four-round KO of another comebacking champ in Mexican Vicente Saldivar, before being stripped in June 1974 for failing to fight Venezuela’s Alfredo Marcano. But he had a good reason: his father was suffering from cancer at the time, and indeed would die later in 1974.

Jofre would box seven more times, finishing aged 40 with a win over decent Mexican Octavio Gomez in October 1976. He quit because he no longer had the ambition to become champion again.

In retirement he became a trainer and developed business interests including owning supermarkets. He parlayed his popularity into a stint as member of Brazil’s Congress and in 1994 was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

He said with justifiable pride, “I would have received much more recognition had I been based in the United States, but I feel very happy being the first fighter from Brazil to be honoured in the Hall of Fame.”

Eder Jofre’s place in boxing history is assured.