And they would’ve got away with it, too, if it wasn’t for these meddling journalists and their blasted exclusives, explains Elliot Worsell

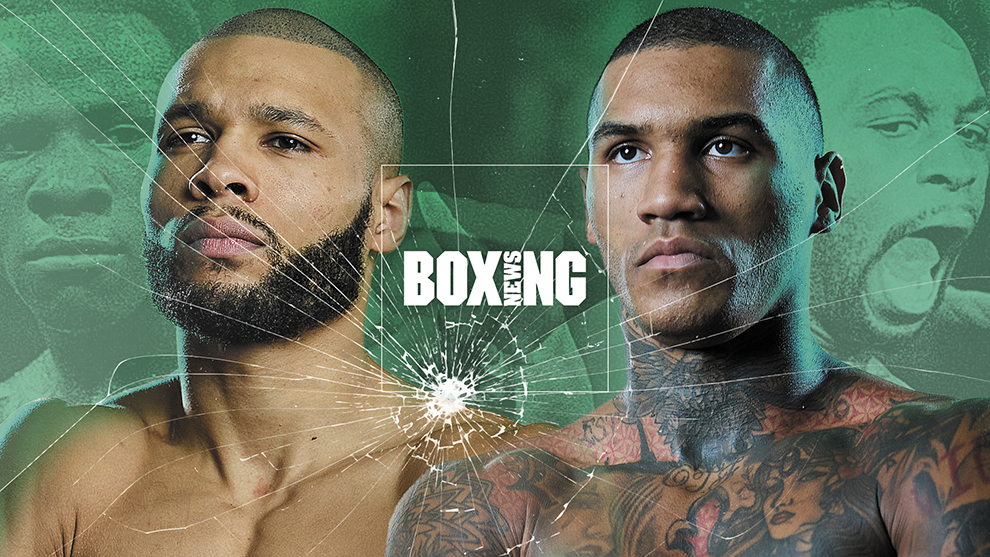

WATCHING Matchroom Boxing’s media workout on Wednesday afternoon, just hours after it had been announced Conor Benn had failed a performance-enhancing drug test (for clomiphene), I couldn’t help comparing it to the scene that unfolds when a family pet dies and the children are then informed of this tragedy upon their return from school.

Usually, such a scenario would be handled with care, and with hugs, and with an explanation, and with honesty. However, like most things, the reaction to it will largely depend on the integrity of the adults involved, as well as how they view the intelligence of their children, meaning there is just as much chance the situation is handled badly, handled, perhaps, the way Saturday’s now-cancelled fight between Conor Benn and Chris Eubank Jnr has been handled.

Which is to say, rather than confront the problem head on with honesty and an apology, the parents will instead welcome their kids home from school as if it were a day like any other. They will then pretend the hamster is still alive and prolong this charade until they are finally able to replace it with one that looks relatively similar, feeling no shame at all.

In fairness to those tasked with upholding the illusion of Benn-Eubank III: Born Rivals going ahead (or simply meaning anything), they did a decent enough job on Wednesday at the workout/wake. Via YouTube, while slumped despondently over my desk, I watched as Darren Barker and Chris Lloyd, presenters for Matchroom Boxing, gave ample coverage to the undercard boxers, none of whom had put the event in jeopardy, and then later interviewed the two main protagonists, Benn and sixty per cent of Eubank Jnr, when the pair eventually turned up. Those interviews were in truth more verbal press releases than interviews in any traditional sense, but that was no fault of the men involved. (All that was revealed was that Eubank Jnr had never received a phone call from Benn, as Benn initially claimed, and that Benn, by his own reckoning, is a “clean fighter” and “not the type”.)

Had they been able to say what they wanted to say, I’ve no doubt the two presenters would have been reading from the same script as everyone else in boxing at two o’clock that day. For it was clear by then that the fight was as dead to Barker and Lloyd, typically so upbeat and passionate, as it was to us. You could hear it in their voices. You could see it in their eyes.

Elsewhere, online, other people had to say stuff because that afternoon something newsworthy had happened and they had a view on it, which, of course, their public needed to hear. This meant, as always, social media became a gathering of oddly opinionated and impatient saints suddenly pretending to care about a sport that doesn’t really deserve anyone’s consideration and maybe, currently, not even their attention. There was, at crisis point, plenty of moral indignation from drug-aided (either physically or financially) fighters who have skeletons of their own, coaches attached to drug cheats (either caught or not), and promoters and managers who would likely behave the exact same way as the promoters and managers involved on Saturday if one of their fighters happened to be in the headline slot.

In fact, what becomes clear and obvious with time is that moral indignation in boxing exists only in moments like this (when something is newsworthy and therefore promises relevance and attention) and is spread only by those who can’t make money from the perceived crime or wrongdoing.

It’s ironic, too, given the criticism they often receive (even yesterday I saw one member of the boxing fraternity lambast them for not asking “tough” questions), that it was a journalist – yes, an actual journalist – who was governing the sport of boxing on Wednesday, and no one else. The name of the journalist is Riath Al-Samarrai and, had it not been for the story he had written in the Daily Mail, there is every chance we would all be none the wiser right now.

Indeed, what was perhaps scariest of all on Wednesday was the feeling that people involved in Saturday’s fight, be it promoters or regulators, had only acted once the information regarding Benn’s failed test had become public knowledge (thanks to Al-Samarrai). That in itself implies all sorts of things and can, if you let it, have you reaching a whole new level of scepticism, paranoia and disillusionment. For if that sort of thing can happen in this instance, why can’t it then happen again? Worse, who’s to say it hasn’t already happened numerous times in the past? (This, remember, is not the first time Al-Samarrai has diligently pursued a PED story involving a high-profile British boxer.)

At the time of writing this, I had no idea if Saturday’s fight would still go ahead, nor did I really care. I’ll be honest, even back when it was signed, safe and sexy, the fight itself – Eubank Jnr vs Benn – did very little for me. It was, to my mind, a fight that should have never happened in the first place, one whose appeal and intrigue was found only in the names and the contracted handicaps, which, such is boxing, became talking points and a way of selling it. (Give the two boxers different names and what do you have? Not a lot. Take away Eubank at sixty per cent and you have even less.)

I would argue as well that while nostalgia is a drug popular with the docile and simple, we can do significantly better than Benn-Eubank III, especially the version of it with which we were left. That, come Thursday, the day it was cancelled, was as dead as the family hamster. It had become an ABBA hologram of a fight, with everything that once made it, at best, unique (the story, the legacy, “Born Rivals”) in the space of 24 hours drained from the fight completely.

That’s how I saw it anyway: a shell, a carcass, a stuffed animal. Also, as much as I tried to understand the motivation for watching it, or maybe attending the fight to report on it (it’s for some a job, after all), there was surely a complicity to now partaking in something like Benn-Eubank III. To do so even behind a scowl, crossed arms, and a fat bottom lip, seemed, to me, a granting of permission of sorts. It was a willingness to acknowledge it existed; a turn towards it rather than away. Most of all, though, to watch it on Saturday, when knowing all we know, would have felt unholy, dirty, and a tad awkward, not unlike attending the funeral of a stranger.

Perhaps tellingly, of all the questions to be answered in the coming days and weeks, the answer I care about the least is the one pertaining to whether Conor Benn is actually a clean athlete or not. There are, for my money, issues far bigger and more important than that which have emerged as a result of his positive test and I’d argue the sadder, scarier stuff heard this week came from others as opposed to Benn. In fact, if Wednesday happened to prove anything it was this: the only thing more problematic and potentially damaging than a dishonest fighter is a dishonest sport, particularly when it’s the sport and not the fighter in charge of the regulations, the punishments, and the setting of standards.

As for Benn and the ramifications of his alleged misdemeanour, only men like Chris van Heerden, a recent Benn opponent, can really pass judgement on this. He took to social media on Wednesday, shortly after the news of Benn’s failed test broke, to write: “How can I not question it (his fight against Benn in April)? Never in my career have I ever been dropped by a punch to the chin. Not by Errol Spence or (Jaron) Ennis or any other fighter.”

Far from accusing, van Heerden is merely trying to make sense of things, as we all are. And while I am, as I’m sure he is, all for the idea of innocent until proven guilty, we must nevertheless remain wary of men in suits brainwashing us into believing the logical next step in any failed-drug-test process is for the accused fighter to clear their name rather than, I don’t know, serve an adequate ban for their transgression.

That campaign – or “case” – has already started with Benn, you can sense it. What has also happened is that the British Boxing Board of Control (BBBofC) have been blamed for spoiling everyone’s fun, despite the fact it was not the BBBofC trying to govern the sport that wrecked everything this weekend but, alas, an adverse finding in a boxer’s VADA (Voluntary Anti-Doping Agency) test. That much, unlike all that followed, is clear, and the only hope now is that the extent of the fallout is not simply a rescheduling of a cancelled fight. For in this scenario, postponement is not a sufficient form of punishment, nor the hoover to suck up dirt and dead hamsters.