No different than most boxers, heavyweights Tyson Fury and Derek Chisora admit the idea of retirement terrifies them, writes Elliot Worsell

OVER the years I have come to realise that the career trajectory of a professional boxer will often mirror the career trajectory of Dirk Diggler from the 1997 film Boogie Nights, with fighting in place of pornography and a gift carried in two fists as opposed to a pair of blue jeans.

It starts, this journey, with a lost soul seeking either a way out or some kind of direction and validation. This then leads them into the arms of the first person who compliments them on their gift, followed by years of using this gift, and honing this gift, to the tune of millions of dollars, a fancy new house and car, numerous awards and trinkets, and a cult of devotees, few of whom really care about the person with the gift.

Inevitably, of course, after a while the thought of using this gift becomes a wearisome one and they feel it is beneath them. By then, typically, they will have developed a drug habit, either recreational or performance-enhancing, they will be tired of accepting awards and trinkets, and they will have both upset many of their old friends, including the ones who cared, and become prey to a new set of friends who manage to care even less about them than the last lot.

This results in them eventually being told, and therefore believing, that they can seamlessly transfer their gift into other pursuits, oblivious to the fact that moving into films or music will require more than just the gift of a large penis. For some reason shocked by this, having been told all they had to do was show up and say their name, the deflated star invariably opts to do more drugs, falls deeper into a depression, and ends up sitting in the cars of men eager to pay to see something now mostly flaccid, asking them, “Do you know who I am?”

These paths, I’ll admit, are not exactly identical. The two professions, despite their many similarities, are in fact quite different. Yet still, in most cases, the journey of a boxer and a porn star tends to conclude with them returning, beaten and bruised not by an opponent but by life, to the very house from which they tried to escape (right into the arms of Burt Reynolds). “I need help,” they will say. “I’m sorry.”

Indeed, it’s the fear of this journey that drives many boxers to fight on longer than they should and many more to return to something they said was over, finished. They find, in retirement, neither the peace nor the attention they felt their achievements in the sport would bring them, and they find as well that few people are as interested in them as a civilian, someone whose gift became impotent the moment it was tucked back inside their jeans, as they were when they wore gloves and punched other human beings.

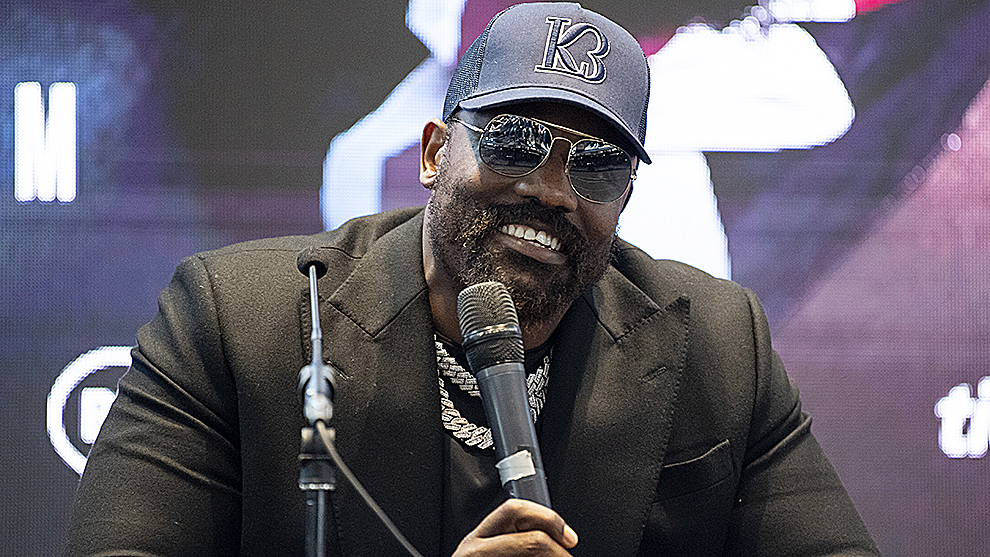

Two boxers keen to delay retirement, even if one appears obsessed with it, are heavyweights Tyson Fury and Derek Chisora. They meet for a third time on December 3 in London and both of them yesterday, on the day they announced this fight, admitted that the prospect of no longer boxing is something that produces in them the kind of fear no opponent has so far managed to replicate.

“I thought about retiring,” said Fury. “I actually did retire (earlier this year) and I really meant it. I know people don’t believe me, but I can put my hand on the Bible and pass a lie detector test. When I said I retired, I really meant it.

“However, I don’t think I can live a normal life. I think I need medical help to be able to do that. If there’s somebody out there who can help me, I need them, because I won’t be able to leave this game and live a normal life unless I’m brain-trained to do that. A normal life is out of order for me. It doesn’t work. I’ll just keep going and keep fighting.

“Ask me what goals I’ve got, or where I want to be in five years, and I have no goals. I’m going to have three fights next year. I guarantee I’ll have three fights next year, starting in February. (Oleksandr) Usyk… and if he wants a rematch, he can have a rematch. (Deontay) Wilder, maybe. Joe Joyce. Daniel Dubois. There’s plenty of British beef to go after. But no (Anthony) Joshua. No more wasting time with idiots. Sorry.”

While it might sound strange to hear Fury reference a wealth of future options when he has just agreed to fight Chisora, a man he has already twice beaten, it is clear, for at least today, that he wants to stick around and remain in the spotlight for as long as he can. This should come as no surprise, either, for the “Gypsy King”s desire for attention has been evident throughout his career, never more so than when he “retires”, and it’s hard to imagine how he survives without it once the curtain falls and the idea of retirement becomes more than just a practical joke or something to write on Twitter to pass the time.

Chisora, too, though arguably less of an attention-seeker, is a man defined entirely by his ability to provide entertainment for a predominantly male audience baying for blood. An unlikely pay-per-view attraction, he is these days accustomed to marching forward, taking punches, and hearing “Ohhhhhh Derek Chisora”, knowing that for as long as he can hear the tune he is both doing reasonably well in a fight and, more importantly, still upright and awake.

“Boxing doesn’t scare me,” he said on Thursday. “If you fight and you get knocked out, it’s the best thing ever. If you get knocked out, you don’t have anything to say. But if you lose a fight on points, you’re pissed. ‘I could have done this. I could have done that.’

“I don’t do that. I’ve been bred to fight and get knocked out. But I don’t see too many who can knock me out. The last one was Dillian Whyte (in 2018).”

With Chisora, one gets the sense his career, much like his fights, will be debated and given licence to continue all the while he stays upright and conscious. He may, sadly, end up being one of those fighters who needs to be put out of his misery in order for him to actually see a way out; a way out, that is, which appears less frightening than the possibility of getting knocked out.

“Let’s be honest, it’s hard,” he said of retirement. “If you come out of boxing and you don’t have anything else on the side going on, it’s so difficult. You know so many boxers who were amazing and then found themselves stuck in the gutter.”

“Do you worry about that?” I asked him.

“Yes,” Chisora said, “I do worry about that. If I said I didn’t worry about it, I’d be a liar. When you’re fighting, everybody wants something off you. When you retire, different animals approach you. They bring with them ideas. Massage your ego. They want your money. But” – he paused to laugh – “I don’t have any money.”