ALL that Bradley Rone wanted was the 800 bucks. That is all and he needed it for a special reason.

Rone had been banned from boxing in Las Vegas, his home. Marc Ratner put the ban in place to try and protect Rone from his bravery and his need. It never worked; Rone went on the heavyweight road.

Rone had fought 53 times and won just seven when the call came in on that July day back in 2003. Rone was at home with his girlfriend, Helen Ruffin. He had no choice, he had to take the fight. It was the following night. Ruffin knew that Rone was banned, she also knew that boxing gave him fast money. He needed it. He was known as TC, short for Top Cat and that is a hard name to pull off when you have lost 26 fights in a row. Rone was a character in the Las Vegas boxing world, the one that has nothing in common with the bright-light charade that dominates when the real champions come to town.

The offer was 800 dollars, the opponent was Bily Zumbrun, and the venue was Cedar City in Utah, which was just under 200 miles away. The local promoter called the night, Ring Devastation. The car journey with Cornelius Boza-Edwards, a truly great former world champion who lives and trains fighters in Las Vegas, was quiet. Rone listened to religious music, sermons and gospel choirs. Boza drove.

Rone had been living for a long time in that awful twilight that so many boxers find is their home when the boxing lights go out. Rone refused to stop, took the fights, made the money and provided promoters with a brave opponent. He fought in Denmark, he fought in Germany and all over America, including Hawaii. “Boxing gave him an opportunity to see the world and make some cash,” said Sean Gibbons, back then a matchmaker on all circuits.

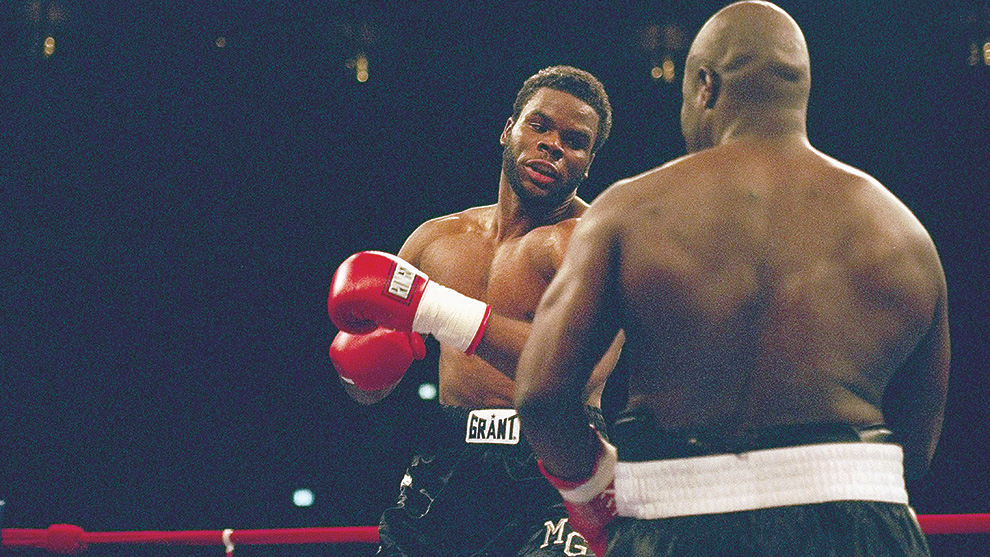

Rone started his career with four losses and was then sent to prison for five years. He was sentenced for assault, having defended the honour of his sister and beaten a man who had beaten her. He returned to the ring when he was released, a few pounds heavier and a lot tougher. He was an invisible fighter on the fringe circuit, occasionally getting the call to meet a contender at either Madison Square Garden or the MGM in Las Vegas. He shared the ring with about 20 quality heavyweights and in one seven-week period he once met Kirk Johnson (15-0), Michael Grant (14-0) and Hasim Rahman (10-0). Only Rahman stopped him; Rone could fight, and he could also eat and party. No crime, but a tough way to make money as a loser on the merciless heavyweight circuit. He picked up money sparring with Lennox Lewis and Mike Tyson in Las Vegas and I know he was used as the first week punchbag.

In Cedar City, before the fight, Boza and Rone had to go and buy the fighter some socks. He was distracted, but that was not unusual.

In the ring against Zumbrun, who had beaten him the previous month over six rounds, Rone did not throw anything in the opening round. He was also not taking any punishment. Rone always had a go, that is why promoters liked booking him. “He was not as strong as he had been in the other fight,” Zumbrun said.

The bell sounded to end the first round, Boza started to climb the steps, Rone turned round and just collapsed. He went down in a heap. No contact, he just fell in a still lump to the canvas. He was down: Bradley Rone, 34, 259 pounds, seven wins in 54 fights. He sure needed those 800 dollars.

The doctor jumped in, an ambulance was ready and Rone was rushed to the local hospital. He was declared dead that night. Heart attack. The day before, he never even knew he was fighting, but that is not the full story.

Boza had no way to contact Rone’s girlfriend, Helen Ruffin. When they looked in his bag, they found just five dollars and her mobile phone. It was left to Gibbons to make his way over to their apartment back in Las Vegas. He was carrying the bad news, a terrible job, an unholy task for anybody. Gibbons might be one of boxing’s truest duckers and divers, but he is not a heartless man. He knew the burden of his gig that night.

Ruffin let him, he told her, she cried and then Gibbons noticed that a new suit and shirt were spread out on the bed. It looked like a welcome home gift for Rone, and it was. And then Gibbons got the story, the real story of Bradley Rone’s last fight.

The previous day, the day Rone had accepted the fight, the boxer was told his mother had died. He was close to her. He needed to get back to Cincinnati, to fly and be with her. And to do that, he needed 800 dollars. The fight was offered four hours later, he accepted. He had his money; he would be with his mother at her funeral. Then he left for Cedar City.

The following week at the Inspirational Baptist Church in Cincinnati there were two open coffins. His mother in one and her devoted big boy Bradley in the other. He had on his new suit, he made it to his mother’s funeral.

At the Landmark Cemetry, the gravediggers had prepared two holes next to each other. “He died of a broken heart,” said his sister, Celeste Moss. The heavyweight also died with just five dollars in his pocket.